On Friday evening October 14, 2011, the restored parlor was officially unveiled to the public. Over 70 members and friends of the museum were present to witness this long-anticipated event. Following is the text of the speech prepared by Executive Director William Tyre which was read just prior to the opening of the parlor doors.

In November 2007, exactly one month after starting my position as executive director at the museum, I received a letter and a donation check from long-time docent and supporter Aileen Mandel. In that letter Aileen expressed her wish that the museum would at long last undertake the important restoration of the Glessner parlor. I immediately contacted Aileen, whom I had known for many years, to enthusiastically let her know that I too had a dream of seeing the parlor returned to its stunning 1892 appearance. Over the next year and a half, two grant proposals were written to underwrite the project but were not accepted.

When Aileen lost her courageous battle with ovarian cancer on June 13, 2009, her children designated Glessner House Museum as one of the organizations to receive memorials. I quickly contacted Aileen’s daughter Ruth, explaining her mother’s particular interest in the parlor, and asking if we could designate memorials toward the project. She enthusiastically agreed, and the fund grew.

Less than a year later, on May 20, 2010, one of our “charter” docents, Bunny Selig, passed away, leaving a sizable unrestricted bequest to the museum. A second bequest was directed to the museum in honor of her long-time friend Robert Irving, with whom she had completed the first docent class in 1971. Bunny had often commented on how horrified Frances Glessner would have been to know we were showing her parlor in such an altered state, so immediately the idea came to mind to use these generous bequests to at last undertake the parlor restoration. The Board of Directors quickly agreed and work began on a year-long project culminating in tonight’s event.

The undertaking was complex – this was not the restoration of just another 1890s interior – it was the recreation of a very specific space designed to the particular taste and sophisticated aesthetic of the Glessners. Fortunately, through photographs and written documentation, we knew a great deal about how the space looked.

The Grammar of Ornament, a Denver-based company specializing in the recreation of historic interiors, had been contracted by the museum in 1991 to create a sample of the 1892 wall covering designed for the room by William Pretyman. You will all recall that sample which hung in the parlor over the doorway to the dining room. In 2010, I called Ken Miller, principal in the firm, to let him know that at long last we were ready to proceed! Fortunately Ken was a patient man, and had carefully kept the files and information ready, hopeful that someday he would have the opportunity to create this unique wall covering. He and his assistant Linda Paulsen meticulously examined an original fragment and historic photographs to determine the intricate process behind the original wall covering. You will hear more about that and about William Pretyman a little later this evening, when our own John Waters presents “Where’s William: In Search of William Pretyman” back in the coach house following the dedication.

Another major element of the parlor design was the beautiful Kennet draperies designed by William Morris. An original fragment of one of these drapery panels survived in the Textile Department of the Art Institute of Chicago. This piece was carefully examined to determine the beautiful and rich colors. Since the fabric was no longer being produced, we turned to David Berman of Trustworth Studios in Plymouth Massachusetts to bring together 19th century design with 21st century technology. Using a digital process, Berman reproduced the intricate pattern and five colors, producing a fabric that is true and accurate to the original. Our own assistant curator, Becky LaBarre, did all the sewing for the panels.

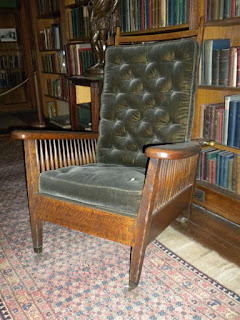

A major piece of furniture for the room had been removed over 100 years ago – the large banquette which occupied much of the south wall of the room. The piece, originally designed for the room in 1887, had apparently been removed by the Glessners about 1905 when John Glessner inherited his parents’ 1830s Empire sofa after the death of his father. We felt that the recreation of this piece was essential to give the room its proper appearance. Long-time volunteer Robert Furhoff, who specializes in historic interiors, spent many hours researching the appropriate construction and fabrics, resulting in a piece that would fool even the Glessners. Scott Chambers of Fine Woodworks Inc. and Gonzalo and Anna Gamez of G&A Upholstery produced a truly beautiful and unique piece of furniture.

Many other small details required attention as well. The drapery rods could be found fairly easily, but the original brackets were heavy and unique in dimensions, requiring the careful attention and craftsmanship of master metal smith John La Monica. The gold leafing of the various elements of the wood trim had deteriorated significantly over the years, and was replaced by Lee Redmond Restorations, who also undertook refinishing of damaged wood mouldings, and refreshing the trim throughout. Jeffrey Ediger of Oak Brothers refinished the surviving metal pieces.

An enjoyable part of the project was bringing the room all back together. This involved a careful analysis of the historic photos of the room, identifying objects that were currently elsewhere in the museum that needed to be returned to the space.

All of the physical work needed to actually restore the room has been undertaken in just four weeks starting with the removal of the old wall covering on September 19th. An outstanding team of craftsmen kept the project on track, so that we only needed to close the room to the public for a little under one month.

As we get ready to unveil the room, a moment to thank those whose generosity has made it possible. As mentioned earlier, Aileen along with her family and friends, spearheaded the project, keeping it in the forefront as we set out goals for the museum. The passing of Bunny brought not only her bequests but additional gifts from her family and friends. As the project grew, the museum approached the Richard H. Driehaus Foundation who generously provided additional support, primarily to produce the Morris draperies. Finally, when the decision was made to recreate the banquette, an anonymous donor stepped forward with a generous gift to our 125th anniversary fund, which was applied for this purpose. Lastly, many of you contributed to this project as well. The remaining funds needed to complete the room were taken from our House and Collections Committee Fund, which is supported by the proceeds from the various private tours and events held several times per year, and which many of you have attended.

At this time, I would like to ask Ruth Mandel to step forward representing her mother Aileen. She is accompanied by her brothers Mark and Eric. In just a moment, Ruth will be asked to cut the teal ribbon on the left doorknob of the parlor. Teal is a special color for Aileen – it is the official color for the fight against ovarian cancer.

I would also like to ask Dina Krause to step forward representing her cousin Bunny Selig, accompanied by Dina’s husband George and their daughter Sydnie. Dina will be asked to cut the purple ribbon on the right doorknob of the parlor. For all of you who knew Bunny, there is no need explain the significance of the purple ribbon.

(At this point, the ribbons were cut, the room was opened and attendees had their first glimpse to view the Glessners’ parlor as it appeared in 1892. Following the viewing of the room, the group reassembled in the coach house where John Waters delivered an informative presentation on decorator William Pretyman).