The light bulb,

the telephone, the automobile, and the phonograph are all ranked among the

greatest inventions of the 19th century. But what about the humble and often

overlooked window screen? Prior to its

introduction during the Civil War, hot weather meant either keeping the windows

and doors of a house closed, or opening them and subjecting the occupants to

wasps, flies, mosquitoes, and a range of potentially infectious diseases. In this article, we will briefly explore the

history of the window screen, and then look at how they were used at the home

of John and Frances Glessner.

EARLY HISTORY

Cheesecloth was

sometimes used to cover windows as a way to keep out insects. Being loosely woven, it allowed air to

circulate, but it was easily torn, soiled quickly, and limited the visibility

from inside. Advertisements for wire

window screens started to appear in the 1820s and 1830s, but the idea didn’t

take off. It was the onset of the Civil

War that made window screens a household word (and necessity).

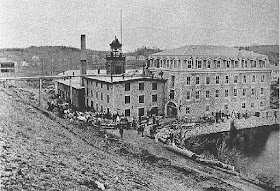

Gilbert and Bennett factory (destroyed by fire in 1874)

Gilbert and

Bennett, a Connecticut based company that made sieves, is generally credited

with the invention of the modern window screen.

The company’s business suffered during the Civil War, as they could no

longer sell their products in the Southern states. An enterprising employee had an idea that

changed history – paint the wire cloth to prevent it from rusting, and sell it

for use as window screens. The idea took

off, and the company made the production of wire cloth a major part of its

business. Homeowners would purchase the

wire cloth and then nail it to wooden window and door frames they

constructed. The firm later introduced

steel wire, which did not rust.

The firm of

Bayley and McCluskey filed a patent in 1868 for screened windows on railroad

cars, which helped to prevent sparks, cinders, and dust from entering the

passenger compartments. Screens were first advertised in the Chicago Tribune in May 1869, the

advertisement reading in part:

“The annoyances of spring and summer,

such as flies, mosquitoes, dust, etc., can be obviated by using the wire window

screens manufactured by Evans & Co., No. 201 Lake street. These can be obtained at fifteen to fifty

cents a foot.”

Window screens

not only made houses more comfortable, they also had a direct impact on health,

as they kept disease-carrying insects out of homes. Over time, the incidents of these diseases

declined dramatically. This aspect of

window screens was considered so important that the Boy Scouts and other

volunteer organizations would help communities install and maintain screens.

PAINTED WINDOW

SCREENS

As was the case

with window shades, artists soon saw the possibilities of window screens, which

were basically canvases with holes in them.

Screens were painted on the outside, normally with landscape scenes,

leaving the holes unobstructed. In

addition to being decorative, the screens were practical as well. From the outside, the painted scenes blocked

the view inside the house, providing a level of privacy.

Painted screen, National Museum of American History

Click here for more images from their collection

Click here for more images from their collection

Painted window

screens became extraordinarily popular in Baltimore, after a Czech immigrant

named William Oktavec painted a screen to advertise produce in his store in

1913. He was soon asked to paint screens

for homes, and other artists jumped on the bandwagon. It is estimated that there were 100,000

painted screens in Baltimore at its peak, many adorning the row houses with

windows at sidewalk level, where privacy was most desired. The screens are considered a Baltimore folk

art and are still produced today, and a collection is displayed at the American

Visionary Art Museum in that city. There

is even The Painted Screen Society of Baltimore, formed to preserve and

encourage the art form.

GLESSNER HOUSE

The building

specifications prepared by H. H. Richardson for Glessner house specifically

include window screens:

“Finish and put up to all the outside

doors and windows, the best patent wire screens, to have steel frames and

hardwood runs, except one window over main stairs on 18th St., one

in library, one in Parlor, two in dining room and one in upper hall. The window screens will be on the

outside. The doors will be made of 1 ¼”

clear pine stock.”

Male servants' door at right, with screen door, 1923

It is

interesting to note that the specifications call for the screens to be on the

outside – an indication that screens were far from being universal at the time,

so the contractors needed to be given extra instruction. One will also note that screens were not put

on every window in the house – the specifications list six windows that would

not have screens, in each case in rooms where there were multiple windows.

This bit of

information relates directly to instructions written by Frances Glessner in

1901 for the servants who were to remain in the house during the summer. She noted:

“When the weather is warm, open the windows

and doors to court yard early in the morning and at about six in the evening –

open only doors and windows which have wire screens. Keep all closed from 9 o’clock in the morning

until six in the evening.”

Screen door for the Prairie Avenue door, in storage in the basement.

Note the custom made wall brackets to hold the door.

Note the custom made wall brackets to hold the door.

E. T. BURROWES

& COMPANY

The screens for

the Glessner house were manufactured by E. T. Burrowes & Co. of Portland,

Maine, the largest manufacturer of window screens in the late 19th

century. They were sold locally through

Robinson & Bishop, the western managers for the company, with offices at

No. 1202 Chamber of Commerce Building.

In October 1893, the firm won the top award at the World’s Columbian

Exposition for their production of wire window screens and screen doors.

The company

noted that “our screens are in use in the best dwellings in every city in the

United States,” listing the homes of Thomas A. Edison, P. T. Barnum, General P.

H. Sheridan, George Westinghouse Jr., and Grover Cleveland in their

advertisements.

In the early

1890s, the company published a 12-page booklet listing the names of hundreds of

Chicago area residents who used Burrowes window screens in their homes. Listed were many Prairie Avenue residents

including George Pullman, Joseph Sears, Philip Armour, and William

Hibbard. The booklet was illustrated

with photographs of thirty houses, including the “Residence of Hon. Robert T.

Lincoln (U.S. Minister to England)” which adorned the cover.

The Glessner

house was illustrated as were several other prominent South Side residences.

2720 S. Prairie Avenue (demolished)

2904 S. Prairie Avenue (demolished)

2838 S. Michigan Avenue (demolished)

1826 S. Michigan Avenue (demolished)

Next time you

open your window on a warm summer day, without the worry of a mosquito flying

in, take a moment to recall the interesting history of one of the most useful

and practical items ever invented to keep our homes safe and comfortable.