Today, December 1, 2020, marks the 96th anniversary of the Glessners deeding their beloved Prairie Avenue home to the Chicago Chapter of the American Institute of Architects (CCAIA), to ensure its preservation. A beautiful toast noting that act of generosity, written and delivered by architect Hermann V. von Holst at the Glessners’ Christmas dinner later that month, was recently acquired for the house collection. Clearly, it was a celebratory month for the Glessners as their friends and the architectural community thanked them for their magnificent gift. In this article, we will reconstruct the month of December 1924, ending with von Holst’s touching tribute to his long-time friends.

THE HOUSE IS GIFTED TO THE CCAIA

During the 1910s and early 1920s,

the Glessners witnessed the enormous change that was happening all around them,

as families left Prairie Avenue and their homes were demolished or converted

into boarding houses or business offices. In 1922, Richardson’s only other

house in Chicago, built for Franklin and Emily MacVeagh at 1400 North Lake

Shore Drive, was razed and replaced with a high-rise apartment house.

The Deed of Gift between the

Glessners and the CCAIA, signed on December 1, 1924, represented the best way

to ensure the preservation of their house, and its continued use by the

architectural community that understood its significance. The Deed was specific

– Richardson’s portrait must always remain on the wall, and his monogram on the

façade must never be altered – but the use of the house would change

dramatically. This was no house museum – the building was to be repurposed for

the uses of the CCAIA to include offices, meeting rooms, gallery space, and an

atelier.

The announcement of the gift was

published in the Chicago newspapers, and within weeks newspapers from across

the country covered the story, a clear indication of how important the house

was considered even at that time. Among the many notes of appreciation the

Glessners received was one from Julia “Lula” Shepley, daughter of Henry Hobson

Richardson and the wife of George Shepley, one of the three men, who, following

Richardson’s death in 1886, reorganized his office as Shepley, Rutan and

Coolidge.

HERMANN V. VON HOLST

An important member of Chicago’s

architectural community in 1924 was Hermann V. von Holst, and he was among the

Glessners’ closest friends. (Read this 2012 blog article for more information on his life and career). Hermann, just

18 years old when he arrived in the U.S. in 1892, accompanied his father, Dr. Hermann

E. von Holst, who had accepted an appointment at the new University of Chicago.

The Glessners quickly formed a friendship with the von Holst family, which also

included Hermann’s mother and sister. Dr. von Holst was forced to retire in

1900 due to ill health. He returned to Germany with his wife and daughter and died

in 1904.

Son Hermann, who by this point was chief draftsman in the Chicago office of Shepley, Rutan and Coolidge, stayed behind and was quickly “adopted” by the Glessners. He starts showing up regularly in Frances Glessner’s journal, attending Sunday suppers or joining them at the symphony. For the first Christmas apart from his family, Hermann was invited to trim the Glessners’ tree on Christmas Eve, and he stayed the night, so that he could “see the fun in the morning.” In a letter from Hermann’s mother to Frances Glessner, dated February 1, 1901, she noted:

“Yes, he is lonely and we, too, miss him greatly. In almost every letter, indeed in every one now, he speaks of your kindness to him and of the enjoyment he receives from his visits with you. It was so very kind of you to have him with you just at Christmas time, for a Christmas spent alone is about the most doleful thing imaginable.”

The Glessners greatly enjoyed surrounding themselves with architects, artists, authors, and musicians, so the friendship is no surprise. But in the case of Hermann, it may well have had added significance. Hermann was born in 1874, the same year as the Glessners’ son, John Francis, who had died at the age of just eight months. In a meaningful way, the young and talented architect may have been a surrogate for the lost son, especially in those first years after George and Frances had both married and were preparing for the holiday in their own homes. (In 1902, on the anniversary of the birth of the infant son, Frances Glessner noted in her journal that he would have been 28 years old had he lived, so his memory always remained with her).

Hermann traveled to Germany to help care for his ailing father in April 1901, remaining for three years, but upon returning to Chicago, he was welcomed again to share in the Glessners’ Christmas festivities, as noted in his reply to Frances Glessner’s invitation for Christmas Day 1904:

“To begin and to close Christmas Day at Mr. and Mrs. Glessners’ – nothing finer could Mr. von Holst wish, and, as the best wishes are so seldom realized, he looks forward with pleasure to the fulfillment of this one: to Breakfast at 8, to Supper at 7.”

His Christmas card from 1909 contains a short but heartfelt greeting:

“To Mrs. Glessner – a Merry Christmas. I know of no truer heart or better friend. Hermann”

It appears Hermann was present every Christmas for decades, even after his marriage to Lucy Hammond in 1911. Soon after, Hermann published Modern American Homes, and one of the first copies was presented to Frances Glessner for Christmas in 1912, with the following, thoughtful inscription:

“To Mrs. Glessner – Your ideals

and ideas for the American Home have ever been an inspiration, to seek and

strive for beauty along simple straightforward lines.”

CHRISTMAS 1924

Frances Glessner’s journal stops

in 1917, but various other documents left behind help us to reconstruct what

Christmas would have been like in 1924. The guest list shows that seventeen

people joined the Glessners for dinner.

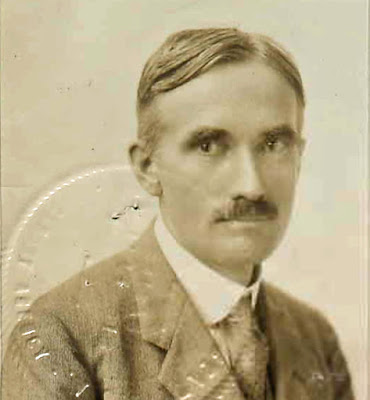

Frederick and Elizabeth Stock – Music

director of the symphony since 1905. On his photo above, which he presented to

the Glessners for Christmas in 1907, he notes that they are his “best friends.”

Frederick and Minnie Wessels – The orchestra’s business manager, and treasurer of the Orchestral Association, of which John Glessner was a trustee.

Henry and Frances Voegeli – The orchestra’s assistant business manager, and assistant treasurer of the Orchestral Association. He took over as business manager upon Wessel’s retirement in 1927.

Eric DeLamarter – Assistant

conductor of the symphony since October 1918.

Enrico and Juliette Tramonti –

They came to Chicago in 1902 when he accepted the position of principal harpist

with the symphony; he continued in that position until 1927.

William and Svea Bernhard – A Chicago architect who later designed the summer home for the Stocks in Ephraim, Wisconsin.

Hermann and Lucy von Holst – Records

indicate that Lucy von Holst, Juliette Tramonti, and Svea Bernhard were regularly

asked to decorate the Glessners’ Christmas tree. All would have been about the

age of the Glessners’ children.

Nathalie Sieboth Kennedy – Reader for Frances Glessner’s Monday Morning Reading Class from 1902 until it was disbanded in 1930. During the 1890s and early 1900s, she was co-principal of the Sieboth-Kennedy School for Girls with her sister Marie (Sieboth) Gookin. It was considered one of Chicago’s finest finishing schools, the graduates “marrying well and early.”

Nathalie Gookin – Mrs. Kennedy’s niece, and the daughter of Frederick and Marie Gookin. Frederick was a close friend of John Glessner, and the long-time curator of Japanese prints and drawings at the Art Institute of Chicago.

Alfred and Vera Wolfe – Vera was the only child of Frederick and Elizabeth Stock. This was the couple’s first Christmas as husband and wife, having been married at Fourth Presbyterian Church in April 1924.

In addition to the guest list, we

also have Frances Glessners’ seating chart. Frederick Stock occupied the place

of honor to her right; Eric DeLamarter sat to her left. The two youngest female

guests, Nathalie Gookin and Vera Wolfe, sat to either side of John Glessner.

The menu was not as elaborate as it would have been in the late 1800s, this time including just four courses (as opposed to eight).

First course

Soup, served with crackers,

olives, and celery. Crackers would have been baked by the cook (no saltines here),

and celery was still quite popular, with special dishes designed to hold the

crudité.

Second course

Turkey, sausage, cranberries, jelly,

sweet potatoes, corn, beans, and radishes. The sausage was most likely from

Deerfoot Farms, the finest and most expensive sausages at the time; it is

frequently identified by name on other dinner menus. Jelly referred to a

gelatin dish, i.e. a “Jello mold,” all the rage at the time.

Third course

Tomato and lettuce salad, with

cheese balls and crackers. Menus consistently show that salad was always served

after the entrée.

Fourth course

Plum pudding, ice cream, cake,

candy, fruit, nuts, and raisins. Plum pudding was a standard on the Glessners’

Christmas table, and ice cream was served at almost all dinner parties.

Beverages

This being Prohibition, no alcohol

was served. During dinner, guests consumed cider and White Rock, the most

popular mineral water of its day. Coffee was served

with dessert.

HERMANN’S TOAST

The toast read by Hermann at

dinner is significant in that it combines a bit of history of his relationship

with the Glessners, how meaningful the years of friendship were to him, and a

first-hand account of how the Glessners’ “spirit” impacted all those around

them.

He begins the toast by noting that

in 1896, he received his first independent commission as an architect from the

Glessners – a bronze tablet commemorating their horse Jim, who had died earlier

that year at The Rocks, where he was buried beneath a huge boulder.

The remainder of the toast makes note of the Glessners’ gift of their Prairie Avenue home and how that act embodied and reflected their generous spirit. The toast reads:

“A few weeks ago, the Chicago papers announced that this home was presented in perpetuity to the (Chicago) Chapter of the American Institute of Architects. The same spirit that remembered the faithful horse with a bronze table dedicated this beautiful structure to posterity, a gift which will have untold influence for good on generations of followers of the art of building.

“The young draughtsman of 1896 has been under the influence of this spirit for 28 years and knows what it has done for him.

“You assembled here know too what a wonderful enlightening factor it has been in your lives. It is a spirit for good and it will outlast this glorious, lovable building. It is the spirit of Christmas that lasts 365 days in the year. Mrs. Glessner and Mr. Glessner are the embodiment of this spirit. They have given the inert materials composing this structure a mighty soul.

“Let us rise and wish them in

unison A MERRY CHRISTMAS.”

And with those carefully chosen words, Hermann V. von Holst preserved the special spirit of this house and its occupants for all of us to appreciate nearly a century later, when the true spirit of Christmas is needed more than ever.

POSTSCRIPT

After dinner, the party traveled

down to Orchestra Hall, where Stock led one of his “popular concerts”

consisting of lighter works, with tickets priced from 15 to 50 cents, making

the concerts available to a wide audience.

On January 1, 1925, to conclude

the celebratory month, the Glessners hosted a reception for the members of the

Chicago Chapter of the American Institute of Architects, assisted by the

Chapter president, Alfred H. Granger. That day was also Frances Glessner’s 77th

birthday.