In

1968, the Glessners’ grandchildren, John Glessner Lee and Martha (Lee)

Batchelder, returned 143 items of furniture and decorative arts to the house,

the first of many donations which have allowed us to restore the interior to

its appearance during the Glessner family occupancy (1887-1936). Among the

items in the first donation was a bronze sculpture of a seated man deep in

thought which until recently was misidentified in the museum database. The

record has been corrected. This is the story of that sculpture.

When the artwork was first accepted for the house in 1968, the donor record listed it simply as a bronze sculpture entitled “The Thinker.” The next year, an appraisal referred to it as the “Scholar.” In 1971, a curator with the Art Institute identified it as “The Thinker,” misattributing it to the Belgian sculptor, Paul Du Bois (1859-1938). Two additional appraisals in 1984 and 1991 identified the sculpture as the “Seated Philosopher,” artist unknown (somewhat surprising given that the name of the artist, P. DUBOIS, is written in large letters on the back side of the sculpture). It is no wonder that there has been some confusion over the years!

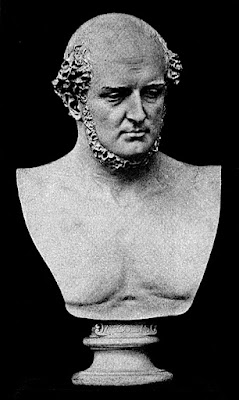

Paul Dubois

The actual artist is Paul Dubois, born in Nogent-sur-Seine, France in 1829. Known primarily as a sculptor, he also achieved later success as a portrait painter. He initially studied law at the request of his father and did not begin his training as a sculptor until the age of 26. Dubois first exhibited at the Paris Salon in 1857, the salon being the official art exhibition of the Academy des Beaux-Arts in Paris, and widely regarded as the greatest annual art event in the Western world at the time. The year after the salon, Dubois entered the atelier of Armand Toussaint at the Ecole des Beaux-Arts.

In 1859, he moved to Italy, which would become his home base for four years, studying and copying great sculptures in Rome, Naples and Florence, leading to his work often being described as neo-Florentine. It was during this time that he created plaster models for two of his best-known works, Saint John the Baptist as a Child and Narcissus, both of which were exhibited at the Paris Salon in 1863. Narcissus was awarded a second prize medal, and the model was purchased by the State. A version executed in marble was later added to the façade of the Louvre Palace.

Bronze copies of both works were made and sold in Europe and the United States. The Glessners acquired a 30-inch copy of Saint John, which they displayed atop a cabinet on the landing of the main staircase, as seen in this image from 1923.

Of St. John, an 1888 article in Harper’s Magazine noted:

“M. Dubois’s St. John, if the allusion may be permitted, was a forerunner in sculpture. By his inspired movement, by the prophetic ardor of his gesture, by his delicate boyish head, with fixed eyes and speaking lips, he carried with him all the young French sculptors, and led them to Florence, where they proclaimed Donatello to be the honored ancestor of modern plastic naturalism.”

Other works by Dubois include Le Chant, installed on the main façade of the Opera Garnier in Paris, and the equestrian statue, Joan of Arc, commissioned by Reims Cathedral and first presented at the Paris Salon in 1889. In addition to the bronze version placed in front of the cathedral, additional copies were made for placement in front of Saint-Augustin Church in Paris and St. Maurice’s Church in Strasbourg. The final copy, a slightly reduced version, was installed in Meridian Hill Park in Washington, D.C. in 1923.

Dubois received many honors in his lifetime and was named a Knight of the Legion of Honor in 1867; in 1889 he was decorated with the Grand Cross of the Legion. In 1873, he was appointed curator of the Luxembourg Museum, and five years later became director of the Ecole des Beaux-Arts, a position he held until his death in 1905.

Tomb of General Christophe Léon Louis Juchault de Lamoricière

Lamoricière was born in Nantes in 1806 and rose in the military ranks during the Algerian campaigns in the 1830s, being appointed a major-general in 1840 and a general of division three years later. He served as minister of war in 1848, but, as a vocal opponent of Louis Napoleon, was arrested and exiled in 1851 after refusing to give his allegiance to Emperor Napoleon III. He was allowed to return to France in 1857 and died at Prouzel in 1865.

The year after his death, a subscription was raised to erect his tomb at Nantes Cathedral. (Officially the Cathedral of St. Peter and St. Paul, work on the building continued for 457 years, commencing in 1434 and finishing in 1891.) The architect of the tomb was Louis Boitte, and Dubois was engaged to design four allegorical statues positioned at each corner of the monument.

(Andrew Dickson White Architectural Photographs Collection, Cornell University)

The 1888 Harper’s Magazine article, quoted earlier, provides a glowing review of Dubois’s work on the tomb:

“(At) the Salon of 1878, M. Dubois exhibited the tomb of General Lamoricière, the result of twelve years’ labor. The work won its author by acclamation the first place amongst living sculptors and classed him on a level with some of the greatest of the past. In this magnificent monument bronze and marble are married with perfect art. The martial figure of the general, draped in his shroud like a soldier in his cloak, rests under a pillared canopy of marble, guarded, as it were, by four seated figures at the angles of the tomb – Faith, Charity, Meditation, and Military Courage.

“Faith, a virginal and pure figure of a maiden, raising with fervor her clasped hands heavenward; Charity, holding in her lap two nurslings, seems like a vision of Andrea del Sarto or of Bernardino Luini realized in sculpture; Meditation, in the guise of an old man with finely intelligent features furrowed by reflection; Military Courage, clad in the armor of a warrior, resting on his sword, pensive and resolute, calm, superb, and strong.

“The Cathedral of Nantes possesses in this monument a work as fine as the finest work of the Renaissance, as fine as the tomb of Louis XII at St. Denis, as fine as the tomb of the Dreux-Brézé at Rouen. Nay, it is even finer, for the life in M. Dubois’s statues is more intense, the moral expression more profound. . . I have compared these statues, to Renaissance statues, but the comparison is only just so far as style and purity of conception are concerned, for M. Dubois’s work is animated by modern sentiment, and impressed with the character of contemporary life and thought.”

The Glessners’ copy of “Meditation”

The tomb was completed in 1879, so reduced versions of Dubois’s four statues were presumably made and offered for sale soon after. The Glessners acquired their copy by 1888, when it shows up on the west bookcase in the library, as circled in red in the photo above. Although the exact circumstances of their acquisition are unknown, several markings on the piece, which measures 13.75” in height, provide clues to its production.

As noted earlier, the artist’s name, P. DUBOIS, is prominently featured on the back side of the stone on which the man is seated. The piece was retailed through Tiffany & Co., the great New York retailer, as noted by its name being stamped in two places on the left side of the base.

The name of the Barbedienne Foundry in Paris can also be found on the left side of the base.

The foundry was started by Ferdinand Barbedienne (1810-1892) in partnership with Achille Collas (see below). The business focused on selling miniature versions of statues from museums across Europe, seeking to democratize art by making it more widely accessibly. Later on, the firm started reproducing works by living artists, most notably Auguste Rodin. Following Barbedienne’s death in 1892, the firm was carried on for another six decades by his nephew, Gustave Leblanc.

Achille Collas (1795-1859) was an important French engineer and inventor who developed a way of mechanically copying sculptures on a reduced scale, a process he called “réduction méchanique” or mechanical reproduction. The resultant popularization of small sculptures and statues literally transformed the bronze industry.

He perfected his mechanical reproduction machine in 1836, and two years later formed his partnership with Barbedienne. Copies could be produced in plaster, wood, ivory, and bronze, the latter being the most common. They soon produced a version of the Venus de Milo, but business remained slow until the firm displayed their work at the Great Exhibition of 1851 in London (also known as the Crystal Palace Exhibition), where it received a special medal. Collas was also awarded a medal in 1855 at the Exposition Universelle in Paris. Business thrived, and the firm had 600 employees by the early 1890s.

The official mark of Collas is set into the back side of the base as shown below. Collas is shown in side profile with REDUCTION MECANIQUE around the perimeter, and his name A. COLLAS below with the added word BREVETE meaning “patented.”

Alternate names

Although

Meditation is clearly the official name of the sculpture, it was

referred to by various names through the years, both in writings and in the

plaques that were sometimes affixed to the copies. (The Glessner version has no

such plaque). Names applied to the artwork through the years include:

-Etude

et meditation (Study and meditation)

-Le

Courage civil ou la Meditation (Civil Courage or Meditation)

-Le

Penseur (The Thinker)

-Wisdom

-Seated

Philosopher

Later History

Dubois’s four statues for Lamoricière’s tomb remained popular, and the full-size plaster models continued to be shown. It appears that more than one version in plaster was created, as subtle variations can be detected in surviving historic images. The illustration above is taken from the official illustrated catalogue of 19th century French sculpture exhibited at the Paris Exhibition of 1900. The undated postcard below, showing both Meditation and Faith, was produced when the models were displayed at the Art Institute of Chicago.

Following Dubois’s death in 1905, his widow donated the 1878 plaster model of Meditation to the municipal museum in Nogent-sur-Seine, France, started by Dubois and fellow sculptor Alfred Boucher in 1902. The museum was decimated by pillagers by the mid-20th century and the artworks were placed in storage for protection. The Musée Dubois-Boucher reopened in 1975 and in 2008 purchased more than 40 artworks by the French sculptor Camille Claudel. Claudel’s childhood home was renovated and expanded, and the current Musée Camille Claudel opened in 2017, housing approximately half of her surviving works, alongside those of Dubois, Boucher, her mentors, and their contemporaries.

Conclusion

The

Glessners’ copy of Meditation, which sits atop the south music cabinet

in the parlor, tells a rich and complex story including the developments in 19th

century French sculpture, the Barbedienne foundry (maker of several pieces in

the Glessner collection), and the widespread availability of reproduced works

of art due to Collas’ invention. The Glessners, who enjoyed studying history

and art, would have been well aware of the story, adding to their enjoyment of

the piece which occupied a place of honor in their home for nearly fifty years.