Portrait of a Man with a Pink is a charming early 16th century painting by the Netherlandish artist Quentin Massys, which has recently gone on display at the Art Institute of Chicago for the first time in many years. The painting was a gift from John J. Glessner, a long-time trustee of the Institute and a close friend of its president, Charles L. Hutchinson. In this article, we will explore the somewhat complicated history of the artwork and how it found its way to Chicago.

Charles Hutchinson and the

growth of the Art Institute

The Art Institute of Chicago emerged out of the Chicago Academy of Fine Arts, formed in 1879. The Academy had acquired the assets of the defunct Chicago Academy of Design, including its leased rooms, artwork, and furniture, and some of its teaching staff. Hutchinson, who was just 25 years old when the Academy of Fine Arts was founded, was deeply involved in both the educational and exhibition aspects of the organization from the beginning, and in 1881 was named vice president. He quickly advocated for a larger permanent location and a name change to the Art Institute of Chicago. The latter was adopted in 1882, the year Hutchinson was elected president.

At that time, there were only

three major art museums in the United States, located in Boston, New York, and

Philadelphia. By the time Hutchinson died in 1924, having served continuously

as president of the Art Institute for 42 years, it was an internationally

recognized museum, thanks to Hutchinson’s boundless vision and determination.

As Celia Hilliard noted of Hutchinson and his contemporaries in her excellent

biography, The Prime Mover: Charles L. Hutchinson and the Making of the Art

Institute of Chicago (Museum Studies 36 No. 1, Art Institute of Chicago,

2010):

“Thanks to their wealth,

these men traveled widely in the United States, and, above all, Europe, where

they were exposed to grand cultural institutions that their fathers could not

have imagined; they returned to their hometowns eager to ‘civilize’ them.

Coming of age at a critical juncture in the lives of their cities, they were

able to help shape these places according to their ideals, founding libraries,

museums, and symphonies – organizations intended to make the elevating forces

of culture available to all. Thanks to their enthusiasm, generosity, and social

connections, their success was unprecedented. Hutchinson, the son of a meat

packer and speculator, stood at the helm of the Midwest’s preeminent museum for

over forty years, and epitomizes these changes. Like his peers, he was a

product of his time and place and, simultaneously, exactly what it needed.”

Growth of the collection

In November 1887, the Art Institute moved into its first permanent building at the southwest corner of Michigan Avenue and Van Buren Street, a Richardsonian Romanesque structure designed by Burnham & Root. Although attendance and membership were strong, the Institute was still relying largely on the exhibition of loaned artworks to draw people through its doors. As Hillard wrote:

“Many great museums are noted

for the buildings they inhabit, but ultimately their quality rests on the

excellence of their collections and the skill with which they are presented.

Thus, during this same period when the grand new home of the Art Institute was

in gestation, Hutchinson also turned his attention to issues of interior design

and presentation, and considered what purchases and gifts might best augment

the museum’s growing reputation.”

This led Hutchinson to make two significant trips to Europe in 1889 and 1890. During the 1889 trip, Hutchinson and his wife visited the Villa di Pratolino outside of Florence, to view an important collection of Dutch and Flemish Old Master paintings that had been assembled by the Russian industrialist Count Nikolay Nikitich Demidov and expanded by his son Anatoly, who had died in 1870. Many of the artworks had been sold off at that time, but a significant collection was bequeathed to Anatoly’s nephew Paul, who sold additional pieces in 1881, retaining thirty of the best works for himself. Paul died in 1885 and his widow sold a few more paintings (now at the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston). By the time Hutchinson arrived in Europe, she had decided to sell the remaining works and engaged the house of Durand-Ruel to negotiate the sale.

Durand-Ruel was the most

important French art dealer in the 19th century. The business had

started as an art shop in 1839 by Jean Marie Fortune Durand and Marie

Ferdinande Ruel. Their son, Paul, took over the business in 1865 at the age of

24, expanding the operation with a larger gallery and advocating for painters of

the Barbizon school. By the late 1880s, Paul’s three sons were actively engaged

in the business, buying Old Masters and continuing their father’s significant

interest in, and support of, the Impressionists. They also expanded to the

United States, opening a gallery in New York, and coordinating exhibitions in

Chicago as early as 1888.

Hutchinson returned to Europe

in 1890 with the goal of coordinating a loan of the Demidov paintings for the

Art Institute. He quickly discovered, however, that a few paintings had already

been sold, and that the works were available for purchase, not loan. He cabled

trustees and friends back in Chicago, including Marshall Field, Philip Armour,

and Sidney Kent, asking if they would purchase the paintings and hold them

until the Art Institute could purchase them, or donors could be found to donate

them. They agreed, and Hutchinson went to Florence to finalize the purchase of

thirteen paintings for $200,000, including works by van Dyck, Hals, Hobbema,

Rembrandt, Rubens, and Steen. Back in Paris, Hutchinson ran into Art Institute

trustee Edson Keith (a Prairie Avenue neighbor of the Glessners), who made the

first gift, acquiring Willem Van Mieris’s canvas, The Happy Mother.

Portrait of a Man with a Pink

comes to Chicago

While at the Durand-Ruel

gallery, Hutchinson noted another painting, Portrait of a Man with a Pink,

attributed to Hans Holbein the Younger. The German artist of the first half of

the 16th century was regarded as one of the greatest portraitists of

his time, and Hutchinson was anxious to have his work represented in the

museum. He acquired the painting, bringing it back to Chicago with the goal of

finding a donor to finance its $4,000 purchase (about $130,000 today).

The portrait, painted between

1500 and 1510, is believed to have been part of the Colonna di Sciarra

collection for many years. The House of Colonna, also known as Sciarrillo or

Sciarra, was an Italian noble family powerful in medieval and Renaissance Rome.

One family member, Oddone Colonna, became Pope Martin V in 1417. By the early

1880s, the painting was owned by Ernest May, a prominent French financier and

art collector. This was the period in which May was shifting his interest to

the Impressionists, including the work of Edgar Degas, who captured May (at

center) in the painting shown below. On June 4, 1890, May sold the Holbein

portrait through Durand-Ruel to Charles Hutchinson for the Art Institute.

Less than a month later, Hutchinson was back in the United States, anxious to share the news of his successful journey with the newspapers. On July 2, 1890, the Chicago Tribune reported:

“Charley Hutchinson is just

in from Europe, fresh as a daisy, and enthusiastic over the art purchases that

Mr. Ryerson and he have made to enrich the growing treasures of the Chicago Art

Institute . . . He feels that what has been bought by Chicago’s committee so

truly represents the Dutch masters that Chicago need not give place even to New

York in the possession of examples of this school of art.”

Members of the press were

invited to view the paintings on November 7, 1890, the day before the

exhibition opened to members. Beautifully displayed in a gallery accented with

palms, ferns, and live music, the paintings impressed the journalist for the Chicago

Tribune, who reported, no doubt to Hutchinson’s satisfaction:

“They are unquestionably the

most representative collection of pictures by the old Dutch masters ever

brought to this country, embracing many works of the first importance, which

the great European museums would be proud to possess and have indeed tried to

secure. They give to Chicago the supremacy among American cities in this

department, and open for our students of art a vast field of profitable study.

Thus the thanks of the community are due to the gentlemen who so promptly and

with such admirable public spirit availed themselves of a unique opportunity.”

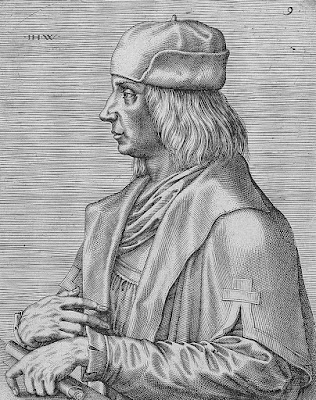

The illustration of the Portrait of a Man with a Pink shown above, was included in the article with the following description:

“The last of the portraits to

be noticed is also the smallest, the others being life-size half-length

figures; and the oldest, belonging to the sixteenth century, while the others

date from the seventeenth. This is the panel by the German master Holbein,

which is a good example of the rigid, literal, sculpturesque style of Henry the

Eighth’s court painter . . . the face is unmistakably, humanly true; one does

not doubt this man’s existence for an instant or miss one note of his rather

strenuous character.”

A question of attribution

The exhibition proved an

enormous success with Chicagoans rightly proud of their “masterly coup.”

However, almost immediately, the authenticity of a few of the works, including

the Holbein, was called into question by an attendee of the opening night

reception. He notified the Chicago Tribune of his opinion, which was

summarily dismissed by the journalist who maintained that the collection

consisted of “first-class examples of the respective painters.”

The Holbein attribution did

receive closer scrutiny, and by the time John Glessner made his anonymous,

retroactive gift of $4,000 in 1894, the painting was attributed simply to the

“Flemish School.” The listing below, taken from the annual report of the Art

Institute issued in 1895, shows the painting as item #1.

In December 1913, the painting received renewed attention when the well-respected art expert, Dr. Abraham Bredius, director of theMauritshuis art museum at The Hague in the Netherlands, toured the Old Masters galleries at the Art Institute. He identified the portrait as the work of Hans Memling (c. 1430-1494), regarded as one of the most important Netherlandish painters of the 15th century. Memling’s art had been rediscovered in the 19th century, so this attribution made the painting far more valuable than the work of an unidentified Flemish artist.

The attribution was short-lived but brought additional attention to the painting. Within a few years, it was conclusively identified as the work of Quentin Massys (also spelled Matsys), a founder of the Antwerp school of painting. Massys was born in Leuven in 1466 and is believed to have attained his master’s status there, before moving to Antwerp, which, by the early 16th century, had become the artistic center of The Netherlands. Massys became one of the first notable artists in Antwerp and was elected a member of the Guild of Saint Luke.

His work is noted for its effects of light and shade, firmness of outline, clear modelling, and thorough finish of detail. His effective use of transparent pigments provided a glowing richness to his paintings that was reminiscent of the work of Memling. He was also known for his “strenuous effort” to express individual character, something clearly seen in the portrait. Massys died in Antwerp in 1530, after enjoying a reputation as a cult figure, and paving the path for a school of painting that culminated with the career of Peter Paul Rubens.

Conclusion

The painting remained

popular, traveling to New York for a loan exhibition in 1929 and to Antwerp in

1930 for the Exposition d’art flamand ancien, showcasing the work of early

Flemish painters. It was exhibited by the Art Institute during the Century of

Progress in both 1933 and 1934 and returned to New York in the years following,

as well as being exhibited in Columbus, Ohio (which, by coincidence, is just an

hour from Zanesville, where John Glessner was born and raised).

Now back on the display in Gallery 207 (The Charles H. and Mary F. S. Worcester Gallery) for the first time in many years, the oil on panel painting, which measures just 11-1/2 by 17-1/4 inches, still captivates with its brilliant use of color, and stark realism. The tag adjacent to the painting reads:

“In this portrait from

relatively early in his career, Quentin Massys followed stylistic conventions

that appealed to Antwerp’s growing market of patrons while also exhibiting the

bold innovations that ultimately made him one of the city’s most influential

painters. The sitter appears frozen in a somewhat unnatural pose, as was the

fashion for half-length portraits at the time, and the positioning of his left

hand on the painting’s lower edge recalls the spatial illusionism found in

portraits by Netherlandish artists of the previous generation. However, the

subtle modeling of the face conveys a strong sense of the sitter’s individual

character at a time when such works tended to idealize their subjects. The

pink, or carnation, held by the sitter could symbolize marriage or Jesus

Christ’s incarnation.”