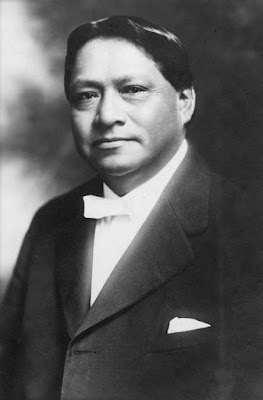

Dr.

Carlos Montezuma, a prominent Chicago physician, full-blooded Apache Indian,

and nationally recognized Native American rights activist, was the guest of the

Glessners for Sunday supper in both 1896 and 1898. Although the exact

circumstances leading to these supper invitations are unknown, Frances Glessner

was clearly impressed with the doctor, then in his early thirties. A signed

copy of a paper Dr. Montezuma delivered in early 1898 remains in the house

archives as a tangible link to the visits by this prominent activist. We

present his extraordinary story and his interaction with the Glessners in honor

of Native American Heritage Month.

Early Years

Carlos

Montezuma was born around the year 1866 near Four Peaks in the Arizona

Territory, located east of present day Phoenix. His given name was Wassaja,

which translates as “signaling” or “beckoning.” Wassaja’s father Co-cu-ye-vah

was a chief of the Yavapai-Apache tribe, and his mother was Thil-ge-ya. In

October 1871, when Wassaja was just five years old, he and other children were

captured for enslavement or bartering by raiders from the Pima tribe. The young

boy was taken to nearby Adamsville where the Italian photographer Carlo Gentile

was at work documenting the local Native Americans. Gentile purchased the boy

for thirty silver dollars, adopted him as his own son, and had him baptized as Carlos

Montezuma – the first name after himself, and the last name as a reminder of

the boy’s cultural heritage, the Montezuma ruins standing nearby.

Carlo

Gentile (1835-1893) was born in Naples, Italy and had traveled the world before

settling in British Columbia, Canada in the 1860s, where he undertook

ethnographic work to document the First Nations peoples, including the Kamloops,

shown below in one of Gentile’s images. In 1867, he relocated to California,

moving back and forth between there and the Arizona Territory, where he

documented the Pima and Maricopa Indians.

After adopting his son, Gentile continued to travel extensively, and by December 1872, the two found themselves in Chicago, where they joined the production of a show entitled “The Scouts of the Prairie, and Red Deviltry As It Is!” at Nixon’s Amphitheatre. The chief draw was Buffalo Bill and “several live Indians,” including Carlos, who was billed as “the young Apache captive, Azteka.” Gentile photographed cast members and sold carte-de-visites (small mounted photos). They traveled with the show until March 1873, and then led a somewhat nomadic life until settling back in Chicago in 1875, where Gentile opened a photographic studio at the southeast corner of State and Washington streets, and Carlos started attending school. Gentile became well-known for his stereo views of Chicago buildings, including the Gardner House hotel at the southwest corner of Michigan Avenue and Jackson Street, shown below.

Schooling

Carlos suffered from a persistent cough, so Gentile sent the boy to a farm near Galesburg, Illinois, where he lived for two years. After returning to Chicago, they resided briefly in Brooklyn and Boston, before settling back in Chicago. Gentile realized that the boy needed a good education, so turned him over to the care of William H. Steadman, a Baptist minister in Urbana, Illinois.

Montezuma

proved to be an outstanding student and graduated with honors from Urbana High

School in 1879, at the age of just thirteen. A year later, he entered the

University of Illinois where he studied English, mathematics, German,

physiology, microscopy, zoology, mineralogy, physics, mental science, logic,

constitutional history, political economy, geology, and chemistry. He was

called Monte by his classmates, and in 1883 began his support for Native

American rights with a speech, “Indian’s Bravery.”

He graduated

from the University in 1884 and returned to Chicago, where he enrolled at the

Chicago Medical College, located at the northeast corner of Prairie Avenue and

26th Street, immediately west of Mercy Hospital. (The college became

affiliated with Northwestern University in 1870, was renamed the Northwestern

University Medical School in 1906, and survives today as the Feinberg School of

Medicine). In 1889, Montezuma received his doctorate in medicine and his

license to practice. Montezuma was the first Native American student at both

the University of Illinois and Northwestern University, and the second Native

American ever to earn a medical degree from an American university. (The first

was a woman, Susan La Flesche).

Medical

practice and Native American activism

Montezuma found a kindred spirit in Richard Henry Pratt, the founder of the Carlisle Indian School in Pennsylvania. Both were strong believers in assimilation as the most advantageous future for Native Americans, Montezuma with his excellent education being a shining example. He began speaking around the country and was quickly offered a position as physician with the Bureau of Indian Affairs. He worked at various reservations in the west, and in 1893 was appointed to a position with the Carlisle Indiana Industrial School, giving him a chance to work closely with Pratt. In that same year, Montezuma’s adoptive father, Carlo Gentile, died in Chicago. He helped support Gentile’s widow and became the custodian of their six-year-old son, also named Carlos.

Montezuma moved permanently to Chicago by 1896, where he established his private medical practice, leasing a suite in the Reliance Building. It was soon after his arrival in the city that the Glessners had an opportunity to invite him for Sunday supper in their home. Frances Glessner wrote an unusually long entry, indicating her deep interest in their house guest and his story. The entry (with a few minor errors) reads as follows:

“Last Sunday (February 23) Mr. and Mrs. Moore, Dr. Dudley, Mr. Hendricks, Prof. and Mrs. Donaldson, Ned Isham and Dr. Montezuma came to supper. Dr. Montezuma is an Apache Indian who was stolen from his tribe when he was five years old by the Pima Indians. He was taken to Mexico and sold to Gentile a photographer who used to live here. Gentile paid thirty dollars for him. He was brought here, educated, and studied medicine. Gentile died leaving a son of seven who was not provided for and Montezuma is now taking charge of him and providing for him. Montezuma is named for the mountain near which he was sold.

“He told us his whole history of his sufferings at being parted from his parents – the wonder and horror of all which he saw in civilization. His tribe were entirely uncivilized, and had no blankets, knives, fire arms or horses. They had never seen a horse or a white man. He thought the horse a part of the man – and had imbued the white man with all kinds of powers. He only patted the earth when a horse came forth, he looked at an Indian only once to kill him. Montezuma saw an immense John Fiske shaped man on his way east in the coach – and thought of course his size came from swallowing children whole. We were all interested extremely by his talk.”

It is

possible that the Glessners became aware of Dr. Montezuma as a result of an

article that appeared in the January 29, 1896 edition of The Inter Ocean,

where he discussed his views on the treatment of Indians:

“The blunder that the government has always made has been in regarding the Indians as a people distinct from other citizens, and giving them practically their own way. They have been isolated in an ignorant and superstitious condition, and the dark picture of their lives cannot be exaggerated. Separated socially and politically from the government under which they lived, they were deprived of forming any ideas of civil law or self government, and their pitiful and helpless condition today may be stated as the result of the government policy toward them.

“If we wish to elevate the rising generation of Indians to a higher and more enlightened condition, we must give them the same chances as have the sons and daughters of other races. The government ought to be more considerate of the true Americans of this country. . . The Indian Bureau has become an absurd and useless institution and absorbs much public money for the little good it does to the Indian. Congress should formulate as soon as possible measures which would allow Indians their full rights and at the same time place their children in public schools in the territory along with the children of others. Every foreigner that lands here has the privilege of our public schools, but the poor Indian is deprived of the advantages of them. These reservation schools are practically worthless and are but a means to continue the reservation system and keep the Indian in continued ignorance and dependence.

“It

is not too late to save the few remnants of our Indian tribes – not, however,

as curiosities, but as self-reliant American men and women. But to do this they

must be treated as a part of the people and be brought into the broad daylight

of American citizenship and equality. This may be a radical step, but it is

their only salvation. Make the Indians citizens, not dependents; given them the

rights and privileges of American manhood, and then let them sink or swim in

the struggle of life.”

In

early 1898, Montezuma delivered a speech for the Young Fortnightly, the junior

branch of The Fortnightly of Chicago, a private women’s club founded to enrich

the intellectual and social life of its members (Frances Glessner was a member).

Entitled “The Indian Problem from An Indian’s Standpoint,” he reiterated his

beliefs as noted above in the 1896 editorial, closing with a plea for proper

education:

“I wish that I could collect all the Indian children, load them in ships at San Francisco, circle them around Cape Horn, pass them through Castle Garden, put them under the same individual care that the children of foreign emigrants have in your public schools, and when they are matured and moderately educated let them do what other men and women do – take care of themselves.

“This would solve the Indian question, would rescue a splendid race from vice, disease, pauperism and death. The benefit would not be all for the Indian. There is something in his character which the interloping white man can always assimilate with profit.”

(NOTE: Castle Garden served as the point of entry for millions of immigrants, prior to the opening of Ellis Island in 1892.)

The printed version of the speech presented to the Glessners with Montezuma’s signature is dated February 10, 1898, just three days before Montezuma’s second supper in their home:

“Last Sunday, Mr. and Mrs. Moore, Mr. and Mrs. Angell, Mr. Hendricks and Mr. Baird came to supper. The guests in the house had heard of Dr. Montezuma and John sent for him to come to supper which he did. They were all much interested in him. He told his story well.”

Later

years

In 1900, Montezuma made the first trip back to Arizona since his childhood, traveling as the team doctor with Coach Pop Warner’s famous Carlisle Indian School football team. He returned in 1903 visiting numerous reservations in the hopes of finding his parents. They were discovered to be long dead, but the visit softened his views of the reservations when he saw how connected his people were to the ancestral land that they called home. He worked to create the Fort McDowell Yavapai Reservation by late 1903, and for the remainder of his life, fought hard for the people in “his” reservation. The next year, he founded the Indian Fellowship League in Chicago, the first urban Indian organization in the United States.

By

1905, his medical practice was thriving, and he moved his offices into Suite

#1108 of the newly constructed Chicago Savings Bank Building, shown below, at

the southwest corner of State and Madison streets. (Now known as the Chicago

Building, the Holabird & Roche designed structure was designated a Chicago

landmark in 1996).

Montezuma attracted national attention as an Indian leader and he delivered impassioned speeches across the country, attacking the government’s treatment of Native Americans and the Bureau of Indian Affairs. In 1911, he helped found the Society of American Indians, the first Indian rights organization created by and for Indians.

Five years later, he began publishing a monthly magazine titled Wassaja (his birth name) that he used to promote his views on Native American education, civil rights, and citizenship. The masthead shown below, taken from the May 1919 edition, shows Montezuma at right holding his pamphlet “Let My People Go.” The notice at the bottom of the page reads:

“Let

My People Go – This little pamphlet has the ring which sounds the keynote of

abolishment of the Indian Bureau and freedom and citizenship for the Indian

race. Buy copies and scatter them to your friends and where they will do the

most good. 10 cents a copy. 3135 So. Park Ave., Chicago, Ill.”

(NOTES: Image courtesy of the Newberry Library, repository of the Carlos Montezuma papers. The address of 3135 South Park Avenue was Montezuma’s home; South Park is now Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., Drive.)

Death and Legacy

Dr. Montezuma

remained active until becoming seriously ill with tuberculosis in 1922. He

moved to the Fort McDowell Yavapai Reservation where he took up residence in a

primitive hut, refusing all medical attention. He died on January 31, 1923 and was

buried in the Ba Dah Mod Jo Cemetery at Fort McDowell.

Carlos Montezuma’s extraordinary story was largely forgotten until rediscovered by historians in the 1970s. Two major biographies have been written:

Carlos Montezuma and the Changing World of American Indians by Peter Iverson (University of New Mexico Press, Albuquerque, 1982)

A Boy Named Beckoning: The True Story of Dr. Carlos Montezuma, Native American Hero (Carolrhoda Books, Minneapolis, 2008)

In 1996, the Fort McDowell Yavapai Nation named their new health care facility the Dr. Carlos Montezuma Wassaja Memorial Health Center. In 2015, the University of Illinois named its newest residence hall Wassaja Hall in his honor.

The

Mitchell Museum of the American Indian in Evanston, Illinois presents the Dr.

Carlos Montezuma Award at its annual gala. This year’s event, taking place on

November 19, 2022, will honor Sharice Davids, a member of the Ho-Chunk Nation

and a U.S. Congresswoman from Kansas, who has continued Montezuma’s work in

advancing Native American rights.