Photo by Hedrich Blessing, 1987

The last

stop on a tour of Glessner House Museum is the school room. Situated at the southeast corner of the

house, it is the only family space located at the basement level. Although more simply finished than other

spaces within the house, in some ways, the school room most effectively shows

Richardson’s brilliance in executing the floor plan for the house, and how

carefully he considered function and circulation. In this article, we will examine those

issues, as well as taking a look at the room as its function changed over the

course of the last 129 years.

A SCHOOL ROOM FOR THE CHILDREN

As

originally designed, the room was to serve as the school room for the Glessners’

two children, George and Fanny, who were aged 16 and 9 respectively at the time

the family moved into the house in December 1887. It is the only room in the house to be finished

in pine. This does not reflect a desire

to cut costs, for even the servants’ bedrooms are trimmed in quarter sawn

oak. The pine is more a reflection of

the overall design of the room, which incorporates many features of the

Colonial Revival that became popular following the centennial of the United

States in 1876. The room is dominated by

a huge paneled fireplace faced in dark brick.

Dentil trim, a beamed ceiling, and fluted pilasters all reflect Richardson’s

interest in using Colonial detailing, and pine was considered the most

appropriate choice for these types of interior spaces.

What is

most impressive about the room, however, is how it is accessed. Located just inside the main entrance of the

house, three doorways enable the room to function as an independent space within

the larger house. The entrance way

leading from the main hall down six steps can be closed off with a paneled pocket

door, making the doorway all but invisible to visitors going up and down the

main stair case. Having the room located

at the front of the house allowed for the friends of the Glessner children to easily

come and go without disrupting activity elsewhere in the house.

A second

doorway, up two steps at the southwest corner of the room, leads to the

entrance from the porte cochere. In this

way, the children and their friends would have had direct access to the

courtyard when the weather was favorable for outdoor activities. This doorway also opens to the base of the

three-story spiral staircase, which allowed the children easy access to their

bedrooms and bathrooms on the second floor.

The third

doorway, at the northwest corner of the room, leads into the basement, accessed

by going up two stairs. The floor level

of the basement is 24” higher than in the schoolroom – which was dug deeper to

permit greater ceiling height in the room.

The first room in the basement off of the school room was possibly used

by George Glessner as a dark room. It is

known that he did develop some of his negatives at home, and the proximity of

this space to the schoolroom, combined with the fact there is only one small

window, would have made it an ideal space for this purpose. Continuing through this room, one has access

to the full basement and then the staircase leading to the kitchen. In this way meals could easily be taken to

the children and their tutor, again without disrupting other activities in the

household.

It is

interesting to note that all three doors in the room are solid oak. In each case, however, the door has been

faced in pine on the school room side – even the door leading into the basement

has the more expensive oak on the basement side of the door – clearly a sign

that pine was not used to save money!

The room

had central heat, as did the rest of the house, but in this space, which is

nearly 50% below ground level, a large radiator was hung on the north wall of

the room, and then covered with a huge brass panel. Presumably that system worked well. The radiator has long since been

disconnected, and, as a result, the room continues to be the coolest in the

house during the winter months.

In

addition to the large work table in the middle of the room (originally the

dining room table in the Glessners’ previous home), ample bookshelves held the

children’s books and other items related to their school work. Numerous cardboard boxes, carefully numbered,

held hundreds of George’s glass plate negatives. Of particular interest, along the north wall

beneath the radiator, was a table which held various pieces of George’s

equipment including a telegraph that connected to several of his friends in the

neighborhood, and a fire alarm that was connected directly to the Chicago Fire

Department. (For more information, see

the blog article “George Glessner and His Love of Technology” dated January 2,

2012).

Not

surprisingly, the room functioned as the center for Christmas celebrations when

the children were young. In December

1888, George photographed the small table-top tree displayed on the school room

table, decorated by the children on Christmas Eve.

THE CHILDREN ARE GROWN

Both

children married in 1898, at which time the Glessners made the decision to

convert the school room into a sitting room.

The central table and its chairs were given to George and his wife

Alice, who returned them to their originally intended use in their dining

room. Plans originally called for an extensive

redecoration of the room, and in January 1899, Frances Glessner noted that

Louis Comfort Tiffany had been consulted about ideas for the space; those plans

were never executed.

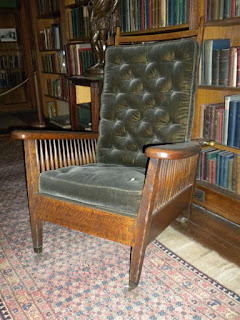

The Glessners

commissioned A. H. Davenport, the Boston-based firm that had made numerous

pieces of furniture for the house when they first moved in, to make new pieces

for the room. The furniture included a

sofa and adjustable back chair, copies of pieces in their library, both covered

in the same cut-velvet fabric, Utrecht, by Morris & Co. A sofa table was designed with a removable

panel on the top to hold books.

LATER HISTORY

The

Lithographic Technical Foundation occupied the house from 1946 until the

mid-1960s. Ironically, they returned the

room to its original function as a class room.

In the image below, taken in 1946 by Hedrich Blessing, the room is

furnished with a series of student desks, suitable for the seminars and other

training sessions held in the house.

After the

house was rescued from demolition in 1966, the school room took on a new use. Given its proximity to the front door, it

functioned perfectly as an office, the executive director and her assistant

easily able to answer the door when visitors arrived, often for impromptu

tours.

By the

mid-1970s, significant work was needed in the room, including the floor which

was badly rotted due to there being only a dirt floor beneath. The entire maple floor and chestnut sleepers

beneath were removed, concrete poured, and a new maple floor installed.

Missing sections of bookcases were recreated,

and repairs were made to the staircase and fireplace.

Eventually,

the offices were moved elsewhere in the building, and the room was restored to

its original appearance as the school room.

Many of the original items, including a Morris Sussex chair, vases,

pictures frames, and numerous books, were returned to the museum by the

Glessner family and were put back into the room, based on the historic photos

taken by George Glessner.

Today, the

school room, with its books and writing tablets spread across the table, gives

the appearance George and Fanny have just stepped out for a few minutes. The space is of special interest to the many

children who visit the house – unable to imagine the idea of their teacher

coming to them, and having a classroom in their own home. It reinforces the importance of education

that the Glessners placed on their children, prompting John Glessner to recall:

“Over the threshold of this has passed a regular

procession of teachers for you – in literature, languages, classical and

modern, mathematics, chemistry, art, and the whole gamut of the humanities and

the practical, considerably beyond the curricula of the High Schools. . . Of

this I am sure, that it gave to each of you a great fund of general

information, a power of observation and of reasoning, an ability and desire for

study, and to be thoroughly proficient in what you might undertake. If ever there was a royal road for that, you

had it . . .”