In this week’s article, we look at the second of

three presidential assassinations to occur during the lifetime of John and

Frances Glessner.

James A. Garfield was

inaugurated the 20th President of the United States on March 4,

1881. Less than four months later, on

July 2, Garfield was shot while walking through the Sixth Street Station of the

Baltimore and Potomac Railroad station in Washington, D.C. The assassin, Charles J. Guiteau, was a

disillusioned Federal office seeker who believed that God had told him to

eliminate the president for the good of the country. Garfield was shot twice – one bullet grazed

his arm, but the second fractured two ribs and lodged behind the pancreas;

doctors were unable to locate and remove it.

Garfield became increasingly ill due to a

serious infection which weakened his heart.

By early September, he was moved to the resort community of Elberon at

Long Branch along the New Jersey shore in the hopes that the fresh air would

aid his recovery, but on September 19, 1881 he suffered a massive heart attack and

died. Guiteau was formally indicted for

murder on October 14, and although his counsel argued using the insanity

defense, he was found guilty on January 5, 1882. He was executed on June 30, 1882.

Due to the extended period between Garfield’s

shooting and his death, the event is mentioned on several occasions in Frances

Glessner’s journal. The first entry is

dated July 2, 1881, the day of the shooting:

“In the afternoon we heard the dreadful news

that Garfield our President has been shot by an assassin named Guiteau. The whole country is in mourning. We all hope he may recover.”

On July 3, she wrote “Garfield better,” but the

next day, “Garfield worse.” On July 10

she noted “Garfield still improving.” The

next journal entry to mention Garfield is dated August 17 when she wrote “The

word is a little better from the President today.”

On September 19, Frances Glessner wrote:

“The last news from the President is that he

cannot live.” A few sentences later, “News

came late this night that the President is dead. Mr. Dinsmore gave me a telegram signed by

Windom, Hunt & Jones.”

The telegram is pasted into Frances Glessner’s

journal. Dated September 18, 1881 from

Long Branch, NJ, it is addressed to W. B. Dinsmore and was received at the Twin

Mountain House in New Hampshire where the Glessner family was summering. Written one day before the president died, it

reads:

“The President had no vigor since yesterday at

two-thirty. He is resting quietly. Those about him are assured he feels his

usual courage and is clear in mind.”

It was sent by William Windom, Secretary of the

Treasury; William H. Hunt, Secretary of the Navy; and Thomas L. James,

Postmaster General.

The next page of the journal contains a

newspaper clipping entitled “Official Bulletin – What a Post Mortem Examination

of the President’s Body Revealed.” The detailed

medical report, dated September 20 at 11:20 p.m. was prepared by the team of

surgeons which attended upon the president.

Their post mortem investigation found that the elusive bullet had

fractured the 11th rib, passed through the spinal column in front of

the spinal canal, and fractured the first lumbar vertebrae. The immediate cause of death was due to a

hemorrhage in one of the mesenteric arteries adjoining the track of the bullet,

resulting in significant blood entering the abdomen.

On September 20, Frances Glessner noted that “we

have our flag (at the Twin Mountain House) draped with black at the front

piazza.” The next day, while traveling

to Goodnow’s Hotel, she noted “The different hotels were all draped with black.”

On September 26, the day of Garfield’s funeral,

the Glessners were in New York on their way back to Chicago. Frances Glessner wrote:

“The city is all closed and draped in mourning

on account of President Garfield’s funeral, which occurred at Cleveland this

afternoon at two o’clock. . . Everyone is sad – and poor Garfield’s picture is

to be seen in every window – sometimes a bronze bas-relief, again an oil

painting or plaster cast. The church

bells were all tolled at two this afternoon – the day was proclaimed one of

national mourning by President Arthur – and all the churches held religious

exercises. The draping on the buildings

was very effective often – notably Tiffany’s which was covered with crape over

the whole front, only drawn aside for the windows to come through.”

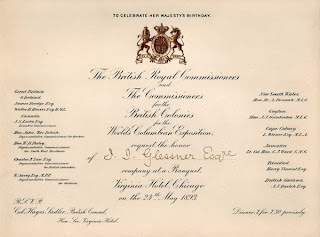

An interesting postscript to Garfield’s

assassination involves two items related to the event. The objects were part of a huge collection of

books and other materials donated by the Glessners’ daughter, Frances Glessner

Lee, to the Harvard Medical School in 1934 when she founded the Magrath Library

of Legal Medicine. The first item, shown

above, is a photograph, one of five taken by Washington photographer C. M. Bell

after the autopsy on Garfield’s body.

The left lateral view of vertebrae shows the assassin’s bullet hole in

Garfield’s spine.

The second item is a leaf from a poem written by

the assassin, Charles Guiteau, while in prison awaiting execution. The poem was part of a small collection of

letters, newspaper clippings, a diary, and other manuscript material assembled

by the Rev. William Watkin Hicks of Washington, D.C. Hicks served as Guiteau’s spiritual advisor

in prison and was a staunch opponent of his execution.

The James A. Garfield Monument, designed by

architect George Keller, was dedicated on Memorial Day 1890 in Lake View

Cemetery in Cleveland, Ohio. These two

views, taken in April 2013, show the exterior of the impressive structure, and the

ceiling of the rotunda.