"Portrait of a Man with a Pink"

Courtesy of the Art Institute of Chicago

Courtesy of the Art Institute of Chicago

Pasted into the

Glessners’ scrapbook is an article from the Chicago

Tribune dated December 28, 1913 entitled “Art Masterpiece Discovered Here.” Written by Harriet Monroe, the article

relates the story of an art expert visiting the Art Institute of Chicago and

identifying a previously unattributed portrait as the work of the 15th

century painter Hans Memling. The

significance to the Glessners lies in the fact that John J. Glessner was the

donor of the artwork. However, the story

and true identity of the artist are more complicated.

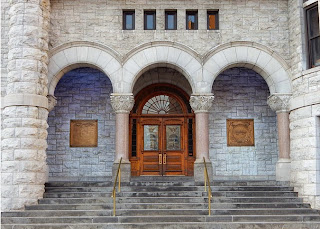

The portrait,

entitled “Portrait of a Man with a Pink” was acquired by Art Institute

president Charles L. Hutchinson in June 1890 through the prominent Paris art

dealer Paul Durand-Ruel. Hutchinson and

his good friend Martin A. Ryerson (a founding trustee of the Art Institute) had

travelled to Europe that summer, returning with an important collection of

Dutch masterworks including the portrait, for which he paid 13,000 francs. It was first put on public display in Chicago

on November 8, 1890 according to a Tribune

article “At the Art Institute”:

“The old paintings by Dutch masters which

were purchased last summer for the Art Institute by Messrs. Hutchinson and

Ryerson were shown yesterday afternoon to the members of the press and will be

exhibited this evening, at the reception which inaugurates the present season,

to the members of the institute, being afterwards accessible to the general

public.

“A view of the paintings confirms the

impression of their importance already gained from the inspection of

photographs and conversations with officers of the institute. They are unquestionably the most

representative collection of pictures by the old Dutch masters ever brought to

this country, embracing many works of the first importance, which the great

European museums would be proud to possess and have indeed tried to

secure. They give to Chicago the

supremacy among American cities in this department, and open for our students

of art a vast field of profitable study.

Thus the thanks of the community are due to the gentlemen who so

promptly and with such admirable public spirit availed themselves of a unique

opportunity.”

1890 illustration from the Chicago Tribune

The collection

of paintings included works by Van Dyck, Hals, and Rubens, as well as the

iconic Rembrandt painting, “Young Woman at an Open Half-Door.” Of the “Portrait of a Man with a Pink,” the

article related:

“The last of the portraits to be noticed

is also the smallest . . . and the oldest, belonging to the sixteenth century.

. . This is the panel by the German master Holbein, which is a good example of

the rigid, literal, sculpturesque style of Henry the Eight’s court painter,

whose portraits form an intimately faithful historical gallery of that dramatic

epoch. His present subject might have

been molded in copper, so dark is his color, or made of leather, so leathery is

his skin. But the face is unmistakably,

humanly true; one does not doubt this man’s existence for an instant or miss

one note of his rather strenuous character.”

When Hutchinson

acquired the portrait, he believed it to be a work of the great German portraitist

Hans Holbein the Younger, who by the mid-1530s had been appointed the “King’s

Painter” to King Henry VIII, chronicling the English court during that

turbulent period. Hutchinson appealed to

his friends to cover the cost of the significant collection of Dutch artworks

he acquired and, in 1894, John Glessner retroactively provided the gift for the

Holbein portrait.

However, at some

point, the attribution of the painting as the work of Holbein was put aside,

and by the early 1900s, the painting was described as the work of an “unknown

Flemish Master.” That changed in 1913

when Dr. Abraham Bredius, director of The Hague Museum, visited the Art

Institute as part of a tour studying Dutch paintings in American collections,

primarily the Rembrandts. The 1913 Tribune article says of his discovery:

“Dr. Bredius’ opinion enriches the institute

collection by a Memling portrait. The ‘Portrait

of a Man,’ hitherto ascribed to an ‘unknown Flemish master,’ which was

presented to the institute nearly twenty years ago by John J. Glessner, is

declared to be an unusually fine example of the work in portraiture of Hans

Memling, the great Flemish master, who died in Bruges about 1492. The picture is worth, therefore, many times

the $4,000 which Mr. Glessner paid for it.”

1913 illustration from the Chicago Tribune

The Memling

attribution was short lived. The

painting was photographed by Braun and reproduced by Max Friedlander in the second

edition of his volume From Jan van Eyck

to Bruegel, published in 1921. It

was Friedlander, generally recognized as the greatest expert of Dutch and German

paintings, who identified the portrait as the work of Quentin Massys.

Quentin Massys

(1466-1530) was a Flemish painter and one of the founders of the Antwerp

school. The portrait, an oil on panel measuring 11 by 17 inches, was painted between 1500 and 1510. As noted in the permanent

collection label for the portrait:

“In the early 16th century,

Antwerp experienced remarkable growth as a commercial center, and Quentin

Massys was one of the most important and innovative of its many painters. In this relatively early and rather damaged

portrait, he followed 15th-century tradition by employing an

immobile pose, barely allowing his subject’s hands to appear above the sill of

the picture frame. Yet Massys developed

a distinctive and nuanced manner of modeling the face, which here conveys a

strong sense of individual character.

The pink, or carnation, held by the sitter could refer to matrimony or

to Christ’s incarnation.”

Regardless of

the controversy over who painted the portrait, it has been recognized as an

important work at the Art Institute since the 1890s, and has been included in

many catalogues of the collection. It

was part of the Art Institute exhibition at A Century of Progress in both 1933

and 1934, and travelled to exhibits in Antwerp and New York. Although it is the only work by Massys at the

Art Institute, it is not currently on exhibit, possibly due to its somewhat

compromised condition. It is hoped,

however, that this significant donation to the collection by John J. Glessner

will once again be put on public display for all to enjoy.