February is Black History Month. The observance goes back to 1926, when the Association for the Study of African American Life and History launched Negro History Week. It took place during the second week of February to coincide with the birthdays of Abraham Lincoln and Frederick Douglass. By the late 1960s, it has evolved into Black History Month, and in 1976 it was officially recognized by the U.S. government for the first time by President Gerald Ford.

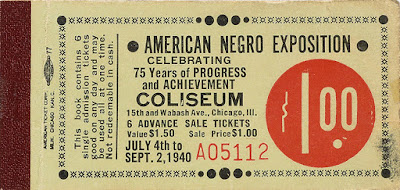

In this article, we are going to explore the history of Chicago’s “forgotten” World’s Fair – the American Negro Exposition of 1940, which took place at the Chicago Coliseum, located just a few blocks from Glessner House, at Wabash Avenue and 15th Street. The event only ran for two months, but took years to plan, and received the endorsement of officials ranging from Mayor Edward J. Kelly of Chicago, all the way up to President Franklin Delano Roosevelt.

The 1933 Chicago World’s

Fair

There was interest in an exhibition noting the accomplishments of African Americans at the 1933 Century of Progress World’s Fair, but the plans never materialized. An exhibition, known as the African and American Negro Exposition, did come together, but it was held two miles from the fairgrounds in the Pythian Temple at 3737 S. State Street, in the heart of Chicago’s Bronzeville community. The site of that Negro Exposition was significant, as the Temple, designed in 1927 by African American architect Walter Thomas Bailey, was promoted as the “largest building financed, designed, and built by black people.” However, its distance from the fairgrounds failed to attract a worldwide audience, with attendees coming mostly from the local black community. (The Temple was razed in 1980).

Planning for the “Black

World’s Fair”

Planning for a much larger fair began in December 1934, just a few months after the Century of Progress closed its second year of operation. In that month, the United Cooperative League of America, Inc. was organized in Chicago, with real estate businessman James W. Washington as founder and first president. Over the next five years, Washington was said to have traveled more than 135,000 miles securing endorsements for what he originally called the “Afra-Merican Emancipation Exposition” to be held in 1940, the 75th anniversary of the emancipation of the slaves at the close of the Civil War. He secured the rental of the Coliseum for $22,500 on his own signature and reputation, and later received an appropriation from the State of Illinois for $75,000 ($1.4 million today) which was later matched by the U.S. Congress.

The headquarters for the Exposition was 3632 South Parkway (the present address would be 3632 S. King Drive although the building no longer stands). This was an important address in the black community as the former three-story stone mansion had been home to the Appomattox Club since 1920. The Club, a social and civic organization, was one of the most important gathering spots in the city for its black business and political leaders. (It closed in the late 1960s).

Washington promoted the Exposition as “the first real NEGRO WORLD’S FAIR in all history” and noted that its objective was to “promote racial understanding and good will; enlighten the world on the contributions of the Negro to civilization and make the Negro conscious of his dramatic progress since emancipation.”

Washington served as president and engaged a young attorney, Truman K. Gibson, Jr., to serve as executive director. The members of the U.S. Auxiliary Committee were personally selected by President Roosevelt and hundreds of endorsements were received, including the American Federation of Labor, the Federal Council of Churches of Christ in America, and the National Red Caps Association (a union of railroad porters and other employees).

Opening of the Exposition

The Exposition officially opened on July 4, 1940 when President Roosevelt pressed a button in his Hyde Park, New York home to turn on the lights. The keynote speaker was Mayor Kelly who noted, in part:

“The nation pays a debt of gratitude to the Negroes today. Not alone for their contributions to the arts and sciences, not alone to the good and great names that stand out in the book of American achievement, but to the great mass of 14 million Negroes who help to form the backbone of American democracy.

“They deserve the good life, because in the greater part, they choose to be the good citizens. They deserve the rewards of democracy because they appreciate so well the blessings of liberty. They have given much, and they are entitled to much.”

The other principal speaker was Senator James M. Slattery, who had introduced the bill in the U.S. Senate calling for the $75,000 appropriation for the Exposition. He noted:

“In this hour we need for all Americans the intense patriotic devotion of the American Negro. In the hour of peril, the American Negro has never failed his country. He will not fail it now. You may spell Afro-American with a hyphen if you will; but there is no hyphen in the Negro’s allegiance to America.”

Tickets cost 25 cents (about $6.50 today) and provided attendees access to over 120 exhibits highlighting the artistic, cultural, industrial, and scientific achievements of the Negro throughout history. Exhibition participants include the major departments of the U.S. government, Tuskegee Institute and Howard University, the Association for Study of Negro Life and History, over 230 Negro newspapers, and companies such as the Columbia Recording Company, Chrysler, Pepsi-Cola, and Firestone Rubber Co. (which funded the Liberia exhibit).

Court of Dioramas

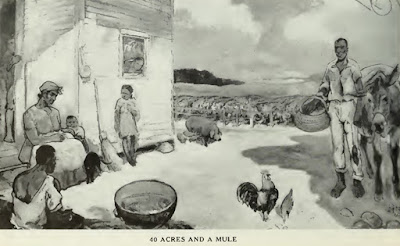

The centerpiece of the Exposition’s main hall was the Court of Dioramas, containing thirty-three dioramas, each five feet wide, created to “illustrate the Negro’s large and valuable contributions to the progress of America and the world.” Crafted of plaster, wood, and Masonite by African Americans, the subject and design of each was overseen by Charles C. Dawson, a graduate of Tuskegee Institute. Subjects ranged from the building of the Sphinx and Ethiopians using the first wheel to Crispus Attucks (the first casualty of the American Revolution) and Matt Henson accompanying Admiral Peary to the North Pole. The Court was centered with a huge model of Lincoln’s Tomb and Monument in Springfield, Illinois.

Surrounding the Court was a series of twenty murals by the talented African American artist William Edouard Scott, a graduate of the School of the Art Institute. Scott was one of the first to depict the “New Negro” in an uplifting way by breaking away from the subjugating images of the past. The subjects of his murals ranged from Chicago’s first permanent settler – Jean Baptiste Point du Sable – trading with the Indians, to Marian Anderson singing the Star-Spangled Banner at the Lincoln Memorial in Washington, D.C.

Tanner Hall

The south hall of the Coliseum contained Tanner Hall, displaying 300 paintings and sculptures and billed as “the greatest collection of Negro art ever assembled.” It was named in honor of artist Henry O. Tanner (1859-1937), regarded as the preeminent Negro artist of his time, and the first to receive international acclaim. Ten of his paintings were displayed.

Also on display in the Hall was the limestone sculpture “Negro Mother and Child” by the African American and Mexican artist Elizabeth Catlett. Completed as her master’s thesis, the artwork won first place at the Exposition.

Other Highlights

The Hall of Fame honored thirty-one outstanding Negroes and their contributions to art, entertainment, literature, industry, and science. Most were depicted in portraits by Persian artist Salvatore Salla. Among those honored in the Hall of Fame were women’s leader Mary McLeod Bethune, labor leader A. Phillip Randolph, athlete Jesse Owens, and architect Paul R. Williams (at the time, the only Negro member of the American Institute of Architects).

Live entertainment could be enjoyed both in the intimate cabaret located above Tanner Hall, and in the immense theatre in the north hall, which sat 4,000 people. Arna Bontemps and Langston Hughes co-wrote “Jubilee: Cavalcade of the Negro” a musical commissioned for the Exposition. Other productions included “Tropics After Dark” and a swing version of “Chimes of Normandy,” a popular French opera. Performers included Duke Ellington, baritone Paul Robeson, and dozens of dancers and choruses. Motion pictures, ranging from entertaining to educational, were screened regularly and included “The Negro in Education” produced by the Rockefeller Foundation.

Literature was another focus and a special book, entitled Cavalcade of the American Negro, was produced by the Illinois Writers’ Project.

Poet Margaret Walker, who became a prominent member of Chicago’s Black Renaissance, contributed a poem which began:

“Come now my brothers and

citizens of America

and hear the strange

singing of me, your brother,

and see the strange

dancing of me, your daughter,

and know that I am you and

you are me

and the two are as one in

danger and in peace,

in plenty and in poverty,

in freedom forever,

in power, and glory and

triumph.”

Every day of the Exposition was designated for a specific state, organization, or theme. Sundays were given over to various Christian denominations from Baptist to Catholic.

On August 21, the Du Sable Memorial Society gave a program honoring Chicago’s first permanent settler. A replica of his cabin, originally made for the 1933-1934 World’s Fair, was reconstructed. The program opened with the signing of “Lift Every Voice and Sing,” noted as the “Negro national anthem,” and featured State Representative Charles Jenkins as the main speaker. (Jenkins had introduced the bill resulting in the $75,000 state appropriation for the Exposition).

The Chicago Defender, Chicago’s leading African American newspaper, sponsored a beauty contest to select Miss Bronze America. The winner, 19-year-old Miriam Ali, used her $300 prize to pay for her tuition at the Illinois State Normal College.

Closing of the Exposition

The Exposition closed on September 2, 1940 with an elaborate program featuring the Democratic nominee for Vice President, Henry A. Wallace, as the keynote speaker (he promised a non-political speech and was elected Vice President two months later). Entertainment including the J. Wesley Jones chorus of 1,000 and selections by Paul Robeson. Organizers had hoped two million people would visit the Exposition, but the exact number of attendees is unknown.

After the Exposition

1940 – Although the Exposition promised to demonstrate great progress for the Negro, with support and cooperation from elected officials, major hurdles remained. On December 31, 1940, less than four months after the Exposition closed, a restrictive covenant went into effect covering the entire neighborhood around the Coliseum, from Roosevelt on the north to Cermak on the south, and State on the west to Lake Michigan on the east. The covenant made residency by anyone possessing 1/8 or more Negro blood illegal. The covenant was to run for twenty years but was nullified in 1948 when the U.S. Supreme Court outlawed restrictive covenants.

1944 – James W. Washington, the “Father of the Exposition,” died unexpectedly. After the close of the Exposition, he formed the American Boystown Corporation to construct Boy’s Town, a home and school near Momence, Illinois, to care for and train underprivileged boys of all races and creeds (like the more famous Boy’s Town in Nebraska). Construction was about to begin at the time of his death.

2005 – Truman K. Gibson, Jr., an attorney, and the executive director of the Exposition, died at the age of 93. Gibson is regarded as one of the unsung heroes of the Civil Rights Movement and served on the “Black Cabinet” of Presidents Roosevelt and Truman. The Black Cabinet was a group of African Americans first assembled by Roosevelt in 1933 to serve as public policy advisors.

2020 – CBS Sunday Morning produced a segment on the conservation of the twenty surviving dioramas from the Exposition, which were acquired by Tuskegee University. The conservation work, begun in 2018 under the direction of Tuskegee’s Legacy Museum curator Dr. Jontyle Robinson, had an unexpected impact. Aware of the fact that less the two percent of conservators in the U.S. were African American, she helped to attract students to the field to work on the dioramas.

Watch the original

six-minute CBS Sunday Morning segment, which aired on August 30, here, and be introduced to LaStarsha McGarity

(shown above), now an Andrew W. Mellon Fellow in Objects Conservation with the

National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C. due to her work in restoring a

diorama.