Chicago in the

1830s was ripe with opportunity. The

population increased at a dramatic rate following the incorporation of Chicago

as a town in 1833 and as a city in 1837.

Scores of men headed west from their homes in New England and the

Mid-Atlantic, seeking their fortune. One

of these men was Thomas Butler Carter.

Thomas Carter

was born in New Jersey on March 26, 1817.

In September 1838 he arrived in Chicago, then a bustling metropolis of

4,000, and just two months later said in a letter home, “but this is destined

to become a great place, and will soon surpass Buffalo.” Carter established his dry goods business, T.

B. Carter & Co. at 118 Lake Street, in the heart of what was then the

business district. His house stood at

the corner of State and Madison.

In 1840, he

married Catherine Raymond, who had been born in 1818 in New York. Catherine’s brother Benjamin Wright Raymond had

been elected mayor of the city of Chicago in 1839 and was just finishing his

first term at the time. He was

re-elected for a second one year term in 1842.

Benjamin Raymond, Mayor of Chicago

1839-1840 and 1842-1843

Carter was a

deeply religious man, and he and his wife were members of First Presbyterian

Church. In June 1842, the Second

Presbyterian Church was organized and they were among the 26 charter members

(Catherine’s brother Benjamin and his wife were charter members as well). Within a few years, he was elected Elder, a

position he held until the 1890s. He

also organized and led the first choir and served as an officer in both the

Chicago Bible Society and the Chicago Sacred Music Society.

By 1847, the

congregation was growing to the point that a new building was needed. Carter served on the building committee, and

he and his fellow committee members were not pleased with the plans they

received from a local architect. Carter

was heading to the East Coast, and agreed to show the plans to a couple of

architects to get their opinion. There

was general agreement that the plans were not sound, and it was recommended

that Carter speak with the New York architect James Renwick, Jr., who had

achieved recognition for his design of Grace Episcopal Church a few years

earlier and had just received the commission to design the Smithsonian

Institution “Castle” in Washington, D.C.

(Renwick received the commission for his best known work, St. Patrick’s

Cathedral in New York City, in 1853). Renwick

agreed to design a new building, working within the $25,000 budget. It would be the first Gothic Revival building

in Chicago, and one of the first buildings constructed of stone in the young

city.

Architect Asher Carter was sent to Chicago to oversee construction of the building, which was completed late in 1850. During this period, Thomas Carter hired Carter to design a new house for him on Wabash Avenue, between Adams and Jackson Streets.

Carter remained

deeply involved in church work. In 1856

he drew up the original papers creating the “Lake Forest Association” which was

a direct outgrowth of his work at Second Presbyterian. The Association oversaw the development of

all the activities in the newly created town, purchasing 7,300 acres of land. Fifty acres were set aside for the university,

and Rev. Robert W. Patterson, pastor at Second Presbyterian, served as its

first president.

Catherine Carter

passed away in 1866 at the age of 48. Soon

after, he retired from the dry goods business, and became connected with the

Equitable Life Insurance Association.

In

1870, he purchased a house at 55 Twentieth Street from James Pattison for $9,000. The house, which now bears the address 215 E.

Cullerton Street, was only two years old at the time, but is now the oldest

surviving home in the Prairie Avenue Historic District on its original site.

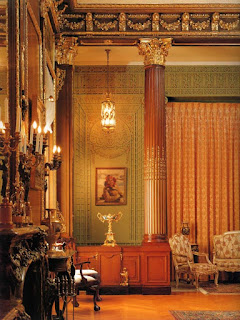

His home, a

three story brick Italianate row house, is a good example of pre-Chicago Fire

architecture. The architect is unknown,

but it possesses all the typical features of this style including tall arched

windows and a projecting cornice supported on pairs of brackets.

The beautiful double front doors were recreated

and installed in January 2006, based on the one and only known historic photo

of the house dating to about 1920.

Immediately

after the Chicago Fire in October 1871, Carter became deeply involved with the

Relief and Aid Society, organized to assist those impacted by the

disaster. In 1874, Carter married Mrs.

Margaret Garthwaite of Newark, New Jersey.

In 1892, Second

Presbyterian celebrated its 50th anniversary, and Carter, as the

last surviving charter member still active in the congregation, compiled and

wrote the history of the church. The

same year, he moved to Evanston, making it his home during the summer months,

and spending the winters in the south.

(The Cullerton Street house was leased for many years and finally sold

by the family in 1925).

Carter and his

wife returned from the South in mid-April 1898, and he was taken seriously ill

soon afterwards, passing away at his Evanston home on April 24 at the age of

81. Funeral services took place at

Second Presbyterian Church and he was laid to rest at Graceland Cemetery beside

his first wife. He was survived by four

children – Frank H. Carter of New York, and Frederic R. B. Carter, Mrs. Lansing

L. Porter, and Mrs. J. H. Nitchie, all of Evanston.

Carter monument at Graceland Cemetery

Mayor Benjamin Raymond is interred in the same plot

Mayor Benjamin Raymond is interred in the same plot

In 1978, a

descendant donated many of his papers to the Newberry Library; the collection is

now known as the Thomas Butler Carter Papers 1831-1898. The papers include many interesting letters

written by Carter to his cousin Aaron Carter in New Jersey throughout that

period, as well as an autobiography Carter penned in 1889, covering his early

life, difficult journey to Chicago in 1838, and his 50 years in Chicago.