The stately Gothic Revival

structure completed for Second Presbyterian Church at the northeast corner of

Wabash and Washington in 1851 was among the most prominent and celebrated buildings

in pre-Fire Chicago. The survival of its walls and 164-foot bell tower made it a

frequently photographed site in the months after the Fire. In this article, we

will examine many aspects of the building – an important work of architect

James Renwick Jr.; a theory as to why the exterior walls survived largely

intact; and what became of the site in the months and years following the great

conflagration that leveled much of Chicago.

Second Presbyterian Church was organized in 1842 with 26 charter members, including Benjamin Raymond, at the time serving his second of two terms as mayor of Chicago. The congregation’s first building was a modest one-story frame structure located at the southeast corner of Randolph and Clark (now part of the site of the Richard J. Daley Center). Within five years, the growth of the congregation and the encroachment of business in this part of downtown resulted in the trustees purchasing a new lot for $5,000 at the northeast corner of Wabash and Washington, in what was then a quiet residential neighborhood. The property backed up to Dearborn Place (now Garland Court) and Dearborn Park, which extended east to Michigan Avenue (and is now the site of the Chicago Cultural Center).

A $100 premium was offered for the best building plan, but only a few were submitted, and none of those proved satisfactory. A church trustee traveling to New York was introduced to architect James Renwick Jr., who was then completing the Church of the Pilgrims on Union Square. Renwick was quickly gaining a reputation for his buildings in the Gothic Revival style, including Grace Church in New York City, and his recently accepted plan for the Smithsonian Institution “Castle” in Washington, D.C. (His best-known work, St. Patrick’s Cathedral in New York City, would follow later, and was constructed between 1858 and 1879).

Renwick accepted the Second Presbyterian commission and the approved budget of $25,000. Soon after, he submitted his sketch for the building, which was to be constructed of “tar rock,” a local limestone quarried about four miles northwest of downtown, noted for its bituminous tar deposits which gave it a spotted appearance (shown below). The stone was quarried, brought to the building lot, and then cut during the fall and winter of 1848. Work on the foundations began in the spring of 1849. This early work was superintended by George Washington Snow, a church trustee and Chicago-based architect remembered today as the inventor of the balloon frame method of constructing wooden buildings.

During the summer of 1849, architect and builder Asher Carter of Morristown, New Jersey, was engaged to oversee the completion of the building. He was the second professional architect to practice in Chicago, and later formed a partnership with Augustus Bauer, designing such well-known buildings as Old St. Patrick’s Catholic Church.

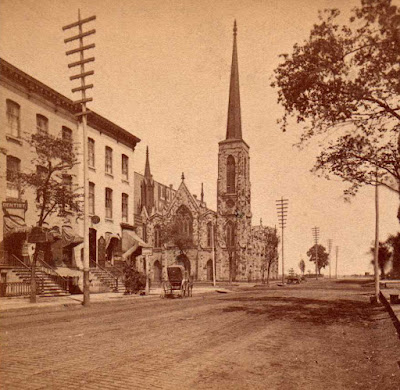

Earliest known photograph of the church. Note the elegant residence at 21 Washington Street shown at far left.

The cornerstone of the church was laid in August 1849 and work was substantially completed by the end of 1850. A service of dedication took place on the evening of Friday, January 24, 1851. The building came in just over the original budget, although the addition of a bell and clock in the bell tower brought the cost to about $35,000. A 50th anniversary history of the church, published in 1892, noted the following about the bell and clock:

“The bell and clock were popular features in the equipment of the church. The bell, key of E flat, large, heavy and rich in tone, was a very important factor in securing the prompt attendance of the congregation at the regular services.

“The clock gave its warning strike when it was time for the pastor to say, ‘In conclusion.’ Occasionally a stranger in the pulpit would prolong his discourse until he saw unmistakable evidence that some of the congregation wanted him to conclude, after the clock had finished striking twelve.”

A newspaper article published in December 1850 noted that “it is perhaps the most magnificent Church edifice in the West.” It is believed to have been one of the first structures in Chicago constructed of stone, predating other buildings erected during the 1850s with “Athens marble,” a limestone quarried in the region of Joliet and Lemont. More importantly, it appears to have been the first building west of New York to have been built in the Gothic Revival style, setting a trend in Chicago (and elsewhere) that continued through the time of the fire.

By the mid-1860s, the church found itself facing the same predicament it had encountered twenty years earlier – namely the encroachment of business into a residential neighborhood. The two maps shown below, dated 1862 and 1869, show this rapid transformation. In the 1862 map, produced by E. Whitefield for Rufus Blanchard, all the lots surrounding the church were occupied by dwellings, except for the Dearborn Seminary - a private school for girls on the west side of Wabash, and an Episcopal church – the Church of the Holy Communion – a few doors north of Second Presbyterian. (That church, visible at far left in the top image of this article, was built in 1859, and abandoned just nine years later when the congregation relocated three miles south).

As seen in the 1869 Sanborn Fire Insurance map, the entire block north of the church had been rebuilt with large commercial blocks. One of the largest was the five-story building for the wholesale druggists Lord & Smith immediately north of the church, which would have blocked all light through the north facing stained glass windows. J. V. Farwell & Co. offered the church $192,000 for its prime corner location – a lot which had cost just $5,000 twenty years earlier.

Church members were divided on what to do. William Bross, then serving as Lieutenant Governor of Illinois, recommended razing the church building and erecting a large business block with stores and offices on the first two floors, and a large auditorium for church purposes on the top floor. (The Methodists did adopt this type of plan and remain to this day in the Chicago Temple on the site of their original church building at Washington and Clark).

The chief objection to remaining at the downtown location was the fact that many of the church members were moving out of the area and relocating to an area two to three miles to the south. It was feared that these members would opt to build a new church convenient to their homes, thus abandoning the old Second Church downtown.

The church as it appeared about 1870. Note the large Lord & Smith building immediately to the north.

Finally, during the summer of 1871, the congregation voted to sell the downtown property for $161,000 to Timothy Wright while retaining ownership of the building itself. A new site was purchased at the corner of Wabash and Twentieth, later exchanged for the present lot at the northwest corner of Michigan and Twentieth (now Cullerton). At the same time, the congregation formally merged with the Olivet Presbyterian Church, at the time located at Wabash and 14th Street, the combined congregation to take possession of the new building upon its completion.

“The rapidity of the growth of this city would seem to be an exhausted theme did not some new occurrence almost daily impress it upon us. The disappearance of one building of note after another, in the more central part of the city, to make room for the raising of one more suitable to commercial needs, is one of the indications . . . Now the obituary of the Second Presbyterian Church, situated on the corner of Washington street and Wabash avenue, must be written. The last gasp was taken by the old church yesterday morning; the old building is dead; decomposition will soon set in.”

A reunion of current and former church members took place on the evening of Tuesday, October 3, after which the building was closed. In the meantime, the trustees continued their efforts to sell the building to someone who would dismantle it and reuse the stone for a new structure.

Use of the bituminous limestone may have been a factor in the survival of the building. An article from the October 26 edition of the Chicago Tribune, however, noted that confusion over the use of the stone and its ability to withstand fire was widespread:

“A writer in the American edition of Chambers Edinburgh Journal, published before the fire, stated that in the neighborhood of Chicago are enormous deposits of ‘oil-bearing limestone,’ of which many houses are built. Inspired by this suggestion, numerous papers are discussing in the East whether the uncontrollable fury of the fire, and the rapid demolition of all our stone structures, were not owing to the use of this bituminous stone. Various buildings are cited, and their speedy destruction looked upon as proof that the intense heat under which they yielded, was due to the presence of the oil in the stone.

“To all of which it is only necessary to state that the supposed oil-bearing stone was not used in this city, except in some cases for foundations, which are all intact, and that the only structure of any size built of that material, was the Second Presbyterian Church, the walls of which are all standing and did not crumble or melt under the heat. The stone mainly used was the Athens marble, a limestone formation, handsome, easily worked, which had become a favorite with builders. Until this fire it had exhibited no special incapacity to resist heat.”

(It is interesting to note that the walls of the present Second Presbyterian Church, constructed of the same bituminous limestone, also survived a devastating fire in March 1900 that completely destroyed the sanctuary and roof).

The church building was quickly put into use. Church member Charles P. Kellogg was the owner of a large clothing manufacturing business which had been burned out in the fire. By the end of October, Kellogg advertised:

“To those of our customers who have been obliged to buy Clothing for the past three weeks in St. Louis, Cincinnati, Milwaukee, St. Paul, Dubuque, St. Joseph, and other inferior markets, we desire to state that we have rented the old Second Presbyterian Church, corner Wabash-av. and Washington-st., which we are now roofing over, making of it as good a store as circumstances will permit. We shall take immediate steps to fill this store with a more desirable stock than ever before exhibited by us, and shall do our whole duty in re-establishing the reputation that this market has always sustained of being the best clothing market in the country.”

The side walls of the church building were 31 feet high, so Kellogg was able to divide the former sanctuary into two floors containing nearly 20,000 square feet of usable space. His company moved into its new building on Madison Street near Market by May 1872, at which time he advertised the former church space for rent.

After the fire, the church collected the insurance proceeds on the building, and the stone became the property of Timothy Wright, who had purchased the land in August 1871. He apparently entered into an agreement with the congregation, as it was noted in August 1872 that “a portion of the stone of the old is being used in the new Second Presbyterian Church, now being rapidly rebuilt, at the corner of Michigan avenue and Twentieth street.”

The building stood largely intact for nearly two years. An article from June 1873 stated that “in the way of ruins our visitors are considerably more than a year too late to see much.” Mention was made of a portion of the Court House which still stood, along with partial walls of the post office and the Grand Central Depot, but the “most picturesque of all the ruins is that of the Second Presbyterian Church.”

By September 1873, demolition of the building was finally underway and by the next month excavation began for a hotel planned by Timothy Wright. During demolition, the cornerstone of the church was located, its tin box containing water-soaked copies of various newspapers and periodicals from 1849, and a Morocco leatherbound pocket Bible.

Wright salvaged much of the stone and transported it to Winnetka, where he intended to build a church in memory of his mother, who had been one of the charter members of Second Presbyterian. The church plan never materialized, and the stone was eventually sold to J. Hall McCormick, who hauled it to Lake Forest with the intention of building a house. His plans changed, and he sold the stone to the trustees of the First Presbyterian Church of Lake Forest, which used it in the construction of its new building, designed by architect Henry Ives Cobb, and dedicated on June 10, 1887. The use was most appropriate as the Lake Forest church had close ties with Second Presbyterian. The Lake Forest Association was begun in the lecture room of the old church in 1856, and three years later the church was organized in the same space.

For unknown reasons,

Wright never moved forward with his plans to build a hotel on the former site

of the church. In December 1876, he sold the land to John Taylor of New York

for $97,500, just 60% of what he had paid for it five years earlier. Taylor

quickly proceeded with the construction of a four-story business block which

cost about $100,000. By October 1877, the building was leased to a large

clothing firm, H. A. Kohn & Bros. (That building was replaced in 1915 by

the Garland Building, a 21-story structure designed by Christian Eckstorm which

still stands).

Perhaps the most interesting part of the building to survive was its wondrous bell, or at least parts of it. During the fire, the bell came crashing down from its perch high up in the tower. It was rescued and found its way to the jewelry firm of I. & C. W. Speer & Co. In February 1872, the firm began advertising that a variety of souvenirs of the fire were being made from the bell. (Souvenirs were also made from the bells salvaged from the Court House and St. Mary’s Church).

“The oldest bells from the great fire are made into charms by the oldest manufacturers, I. & C. W. Speer & Co., established 1843. They are now making twenty-five different kinds of charms, including the beautiful paper weight, the cow kicking over the lamp; beautiful Bibles, with date of fire on the cover; bells, book-marks, tea-bells, and all other charms from the famous old Second Presbyterian Church bell, which was the first that rang the fire alarms, by authority of the city of Chicago.”

ADDITIONAL IMAGES SHOWING THE BUILDING AFTER THE FIRE

The First National Bank, seen through the front entrance of the church, was one of the few buildings in downtown Chicago to survive largely intact.