The sale of the house by the Graphic Arts Technical Foundation (GATF), which had occupied the building since 1945, did not come as a surprise to those in the architectural and emerging preservation communities. In November 1963, a meeting took place between two senior staff members of GATF and Wilbert R. Hasbrouck (Chairman of the Preservation Committee of the Chicago Chapter of the American Institute of Architects), Joseph Benson (Secretary of the Commission on Chicago Architectural Landmarks), and Marian Despres (early Chicago preservationist and wife of Alderman Leon Despres, who drafted the city's first landmarks ordinance). It was at that meeting that GATF announced its plans to relocate operations to Pennsylvania and put Glessner House up for sale. Hasbrouck reported back to Jack Train, president of the Chicago Chapter AIA:

"Regardless of what final use is made of this building, I feel the AIA must take a major advisory role in its disposition. The Glessner House is too important a structure to go the way of the Garrick." (This was a reference to Adler & Sullivan's Garrick Theater, razed in 1961 after a significant battle that helped galvanize Chicago's early preservationists. A number of the individuals who fought to save the Garrick played a leading role in successfully saving Glessner House).

Turning back the clock 55 years to January 31, 1965, if you were to have picked up the morning edition of the Chicago Tribune and turned to page S3, you would have read the following article about the house. It may well have also been your first introduction to John and Frances Glessner, whose names had slipped into obscurity after their deaths three decades earlier.

Old Show Place on Prairie Avenue Haunted by Shaky Future; Now for Sale

Architects Hope to Make It a Museum

by Sylvia Shepherd

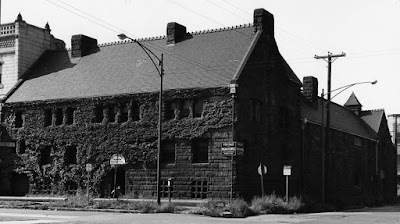

Granite block old home of late J. J. Glessner at 1800 Prairie av.,

was built in 1886 and has survived decline of once-fashionable

south side gold coast. Fate of house worries history-

conscious Chicagoans.

was built in 1886 and has survived decline of once-fashionable

south side gold coast. Fate of house worries history-

conscious Chicagoans.

The uncertain destiny of the old J. J. Glessner house, built almost 80 years ago at 1800 Prairie av., has aroused the fears of several history-conscious Chicagoans.

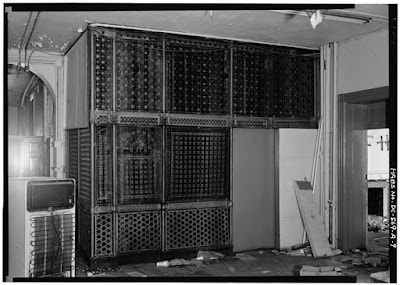

The house, one of the show places of the original south side gold coast, now holds the Graphic Arts Technical Foundation. This research organization has moved most of its operations to a new headquarters in Pittsburgh and wants to sell the Glessner building.

Richardson's Last Work

William Hasbrook (sic), one of those interested in preserving the building, said the Glessner house "would make a small museum of architecture." Hasbrook is chairman of the committee for preservation of historical buildings for the local chapter of the American Institute of Architects.

Hasbrook believes the house is the only remaining residential work of the late Henry Hobson Richardson, famous Boston architect, in this city.

"Chicago is known thruout the world for architecture - not only of the past but of the present," said Hasbrook. "Material on architectural history is scattered around the city - in bits and pieces. This house could become a central spot for this material."

Mrs. Leon DePres (sic) wife of the 5th ward alderman, said, "Anything could happen to the building. There's no protection for it."

"We must see what we can do to preserve it," she added. "It could be a future attraction for tourists."

A City Landmark

Also interested in preserving the building is the Commission on Chicago Architectural Landmarks. Joseph Benson, commission secretary, said his group is "very concerned" about the fate of the house, which is one of 39 official landmarks in the city.

Richardson built the house in 1886 in what came to be known as "Richardsonian Romanesque." Because the architect believed beauty to be found in strength, granite blocks were used in the construction. He died three weeks after completing the house.

John J. Glessner was born in Zanesville, O., and came to this city as a young man. When International Harvester company was founded in 1902, he was a founder and became a vice president.

Glessner and his wife, Frances, were social leaders for 60 years. The house was famous for architectural significance and hospitality.

Glessner was a board president of Rush Medical college, a director of the Chicago Relief and Aid society, and a trustee of the Chicago Orphan asylum, the Chicago Orchestral association, and the Art Institute.

Society Rendezvous

His wife's Monday Morning Reading class was a feature of south side society for 50 years. Most of the fashionable women of the city began gathering at 10:30 a.m. until a class of more than 40 was assembled in the long library.

It was to their home that the Chicago Symphony orchestra members came once a year for a party.

Mrs. Glessner once was quoted as saying, "For all its granite, this home is wonderfully elastic. You can squeeze as many as you want into it."

In 1924, Glessner announced that the house would be given to the American Institute of Architects after the deaths of himself and his wife. His will asked for its maintenance as "a museum, library, gallery, and educational institution, including a school of design for legitimate architectural assemblages."

Rich Social Background

By 1925, a reporter wrote, "The antennae of business have encroached all round and about the dignified granite residence." Already changing was the neighborhood which once housed the George M. Pullmans, the Marshall Fields, T. B. Blackstone, the elder Philip Armours, and Dr. Frank Billings.

Mrs. Glessner died in 1932 at the age of 84. Her husband died just before his 93d birthday in 1936.

Conforming to the request in Glessner's will was deemed too costly in 1937 by the A. I. A., which estimated remodeling expenses at $25,000. It returned the home to the Glessner estate, whose heirs decided in 1938 to give the building to the Armour Institute of Technology.

"It is still in excellent shape" said Hasbrook, "and a choice piece of property."

Corrections to 1965 article:

- Henry Hobson Richardson died in April 1886, three weeks after completing the design for the house. The house itself was completed in time for the Glessners to move in on December 1, 1887.

- The Glessners invited the entire Chicago Symphony Orchestra for dinner on three occasions. Smaller dinners for the music director, selected orchestra members, and visiting soloists were held frequently.