INTRODUCTION

Last month, we introduced a delightful paper, A Summer with Birds, Bees and Blossoms, which Frances Glessner prepared for a presentation at The Fortnightly of Chicago in November 1903. Recording the idyllic summers spent at her beloved summer estate, The Rocks, in the White Mountains of New Hampshire, she focused on her keen observations of the endless varieties of birds which called the estate home (the topic of Part I), and her many years of caring for her bee colonies (the topic of this article).

Frances

Glessner began keeping bees at The Rocks in May 1895 as noted by this entry in

her journal:

“Friday,

Mr. Goodrich brought out my bees – two colonies. They were set up in the summer

house in front of the house. We watched him open the hives. He showed us all

through the hives and clipped the queen’s wings.”

The record of her endless labors caring for the hives fill many pages of the journal over the next fifteen years. Also tucked into the journal are countless letters from friends and family who were the grateful recipients of the treasured jars of honey. By the summer of 1909, it was determined that the physical exertion in maintaining the hives was becoming too much for her to handle. Dr. James B. Paige from the University of Massachusetts at Amherst, upon her invitation, came to inspect the hives and accepted them for the school. (Beekeeping is still taught there).

A SUMMER WITH BIRDS, BEES AND BLOSSOMS

The following excerpts are taken directly from Frances Glessner’s paper.

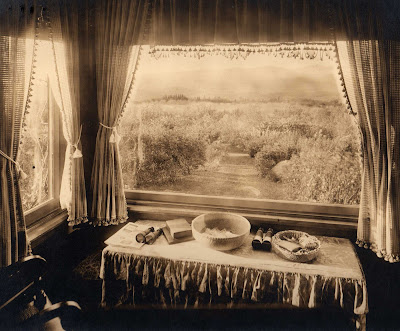

Many, many hours of daylight are spent in the little bee house on the gentle slope of our home hill near where the rainbow rested. This bee house was built for me by a dear friend, a friend who had a poet’s soul if not a poet’s song. Carved on the beams by his own hands are sentiments which belong with the place and its uses.

“As

bees fly hame wi’ lades of treasure,

The

minutes wing their way wi’ pleasure.”

(Robert

Burns)

“Tis

sweet to be awakened by the lark, or lulled by falling waters,

Sweet

the hum of bees, the voice of girls, the song of birds,

The

lisp of children, and their earliest words.”

(Lord

Byron)

And again towards the east –

“But,

look! The morning sun in russet mantle clad

Walks

o’er the dew of yon high eastern hill.”

(Shakespeare,

Hamlet)

And last –

“To

business that we love we rise betimes and go to it with delight.”

(Shakespeare,

Antony and Cleopatra)

Many, many times have I been asked whatever put the honeybee in my bonnet.

One of my very earliest recollections is of Aunt Betsy’s garden. Dear old Aunt Betsy and her dear old garden, with paths to get about in, and all of the rest of it roses, and tulips and daffodils, and altheas, and gooseberry and currant bushes, and a long grape arbor, and peach trees and lilac bushes . . . There were no weeds, but there was a glorious tangle.

Off

in one corner was a row of white beehives. Under the grape arbor stood a huge

bee palace. The bees were the greatest fascination to me, and when Aunt Betsy*

took me into the inner cupboard of a closet in one corner of the sitting-room,

where was kept not only the best white and gold china, but also her whole

precious store of white and gold honey, and allowed me to cut off all I wanted

for my supper, I then and there inwardly vowed “when I grow up I will keep

bees.”

My

opportunity for cultivating the science of apiculture did not come until nine

years ago. I had no notion of how to go about it, but consulted the book-store

– the place one generally goes for information. There I found there were bee

journals published, and books about bees to be had, and incidentally learned

that there were beekeepers’ conventions, and dealers in beekeepers’ supplies,

and other sources from which one could get more or less correct information. I subscribed

for four bee journals, bought two big bee books, and during that first winter

read everything on the subject I could lay my hands on. Later on I joined an

association of beekeepers.

I bought two fine colonies from a beekeeper in Vermont, who came over with them himself, shipping the bees by express, the hives carefully closed up so the bees could not escape, the bee man traveling on the same train with them in order to look after them at stations where they were they were transferred. When the old man said good-bye and left me the real owner of two colonies of Italian bees, I felt quite overwhelmed with doubt and responsibility; for reading a theoretical book by the cosy fire in one’s library is a very different proposition from the practical manipulation of a seething, boiling mass of bees.

Was

it Pliny the elder who said long ages ago before it became a Dutch proverb, “He

who would gather honey must brave the sting of bees.” Am I often stung? Many,

many, many times, but there is this comfort – the sting is acutely painful, but

one gets inoculated with the poison, so after frequent stinging, beyond the

first hour’s pain, there is no swelling nor irritation, and then bee stings are

said to be a cure for rheumatism.

Nectar

has a raw, rank taste, generally of the flavor and odor of the blossom from

which it is gathered. Formic acid is added to this raw product by the bees

before it is stored in the cells; it is then evaporated by the fanning of the

wings of that portion of the colony whose duty it is to ventilate the hive. After

the honey is evaporated and the cells filled to the brim, they are then sealed

up or capped over with wax. Wax is a secretion from the bee itself, a little

tallow-like flake which exudes from the segments of the abdomen.

Bees do not make honey, they simply carry it in from the blossoms. Not all plants are honey plants. Many of the best and richest blossoms are small and insignificant. In the region of the White Hills, there are about forty varieties of plants which produce honey. Each kind of honey has its own distinct flavor if the plant producing it is in sufficient quantity for the bees to work upon that plant alone, such as raspberry, clover, linden, buckwheat. When no great honey yielder is in bloom, the bees will carry nectar from all available blossoms, giving a very agreeable mixture. We grow a large bed of borage and another of mignonette for the exclusive use of the bees, the mignonette giving a most marked flavor of the flower from which it is gathered. Goldenrod honey is as yellow as the flower itself, and very strong in flavor and sweetness.

Bees

fly in a radius of about two miles from their own home. Many times have I

jumped from the buckboard when driving and examined the bees on the blossoms by

the roadside to find they were members of my own family. My bees are the only

Italians in the neighborhood, so we know them by their color, and I think know

them by their hum.

A

worker bee in its whole life will carry in one-thirtieth of an ounce of honey –

that is, it is the life work of thirty bees to carry in one ounce of honey –

that of all the foods in the world this is the most poetic, delicious, and

natural, a pound of honey has never realized its value in money. The gathering

of a one-pound section would wear out the lives of five hundred bees. Bradford

Torrey asked me last season if I had any commercial return from my honey. I

told him that I gave it to my friends. “Oh, then you have!”

Working with and manipulating bees has been made possible by the invention and use of a smoker. Smoke from old dry wood burning in this is puffed in at the entrance of the hive, alarming and subduing the bees, so that they may be handled with comparative comfort. A veil of black net is worn over the hat and face to protect one from stings.

I

said in my haste all men are cowards about working among bees, but that isn’t

quite so. They are by no means brave. It is the duty of some special workman to

keep an eye on my bees during June and July to watch for swarms while I am

forced to be away. Let any commotion arise among the hives, the man usually

rushes to the house, with his eyes fairly bulging out of his head, tells me as

quickly as possible that the bees are swarming, and then he seems to melt into

the earth. While I rarely need the services of a man in doing any of the work,

it is amusing to a degree to see them take to their heels and run like kill

deer if any of my bees so much as makes a tour of investigation about their

heads. A man who faces a bear with delight will turn pale with terror at the

thought of a bee sting.

There

is very much labor connected with an apiary, and constant confinement in

daylight. My best honey record for one season was a fraction over one thousand

pounds from six colonies. Seven hundred and seven of these were sections of

comb honey; the balance was extracted honey. By this, I mean that honey which

had been stored in brood frames was uncapped on both sides with a sharp knife,

the frames then placed in a large barrel-shaped extractor, which held three

frames at one time, the wire baskets containing the frames were turned rapidly,

and the honey thrown from the cells by centrifugal force, and then drawn off below

into glass jars.

In September, each one of my little families is carefully weighed. Those which do not tip the beam at fifty pounds or more, are fed with sugar-syrup or honey until the weight is sufficient to ensure them abundant food during the long winter. When settled for the winter they cluster in an oval mass, one bee over-lapping another, the food being passed from one to the other. They are not dormant in the winter but are quiescent.

Tell

me when you taste your tea biscuit this afternoon, spread with nectar stored by

my New Hampshire pets, and which has in it a touch of wild rose, flowering

grape, red raspberry, a dash of mignonette, and all the rest gathered from

luscious heads of white clover, did not these patient little workers find for

you and me the pots of gold which were hidden where the rainbow rested on the

hillside one smiling and tearful day in June twenty years ago.

PRESENTATION

AND RECEPTION

Frances

Glessner completed her paper by the time she returned to Chicago from The Rocks

in October. Postcards were sent out to members of The Fortnightly announcing

the program. Soon after, she became seriously ill, so much so that she was

unable to deliver her paper.

Nathalie

Sieboth Kennedy (above), the reader for the Monday Morning Reading Class (and

later president of The Fortnightly), was asked to deliver the paper, and the

program proceeded as planned in The Fortnightly rooms at the Fine Arts Building

(below).

The

paper was well received by the members, as recorded in the numerous letters

Frances Glessner received afterwards. From these we learn that she also

provided an observation hive, enclosed in a glass case. Her cook, Mattie

Williamson, prepared her award-winning biscuits which were enjoyed with honey

from The Rocks. Members of the Reading Class provided yellow chrysanthemums

which were arranged around the observation hive; following the talk they were

sent to Frances Glessner along with sincere wishes for a speedy recovery.

A few quotes from the letters speak not only to the quality of the paper prepared, but also of the high esteem in which Frances Glessner was held by her many friends.

“I

must tell you, though I am sure you know it without words of mine, how the

rare, delicate beauty of your paper satisfied and charmed me. It was so

unusual, so simple and natural, so exquisite, that I can not express the joy it

gave me. It gave everyone the same pleasure. I never saw the Fortnightly so

full of a sweet genuine delight. Every word rang so true, called up such pure

beauty, revealed such lore of nature, and brought us all to the natural world,

as a ramble in the very haunts that you described might bring us.”

(Kate

P. Merrill)

“How

did you write of your own experience and out of your own full heart and still

keep yourself in the background so completely and throw into the foreground the

little creatures you so dearly love so that we who listened felt that we were

partakers with you in their joys and sorrows?”

(Louise

T. Goldsmith)

“I

feel very humble for not having known all the things you could do. I knew you

were angel-good, as the Germans say, to all your world (as well as that of the

other half) about you and that there are many, many of us to whom you make life

much pleasanter and happier by your thoughtfulness. But I didn’t know that you

could put words together to make really true literature as much as Olive Thomas

Miller or John Burroughs or any of the rest of them.”

(Emma

G. Shorey)

CONCLUSION

During her ongoing illness, Frances Glessner reworked the paper into a book which she presented to her five grandchildren. The dedication reads:

“To my five grandchildren, whose prattling tongues and toddling feet are now bringing the same joy and sunshine into my summer home as did their mother and father, my own girl and boy, at their age a generation ago, this little book is lovingly dedicated.”

The original paper was delivered again many years later, at some point after World War I, as indicated by an addendum to the paper:

“You

know about the ‘proof of the pudding.’ Well, we did not have many puddings in

war times, but there never was any restrictions on the use of honey. My work in

the apiary taught me that honey is a delicious and practical sweet for making

puddings and ice creams, and in any kind of cooking.”

The

bee house returned to its original use as a “summer house” after the hives were

taken away in 1909. In 1937, the year after John Glessner died, his daughter-in-law

Alice had a large in-ground pool constructed next to the bee house, which was

converted into a pool house. In 2003, several Glessner descendants funded the

restoration of the bee house, and it remains today as one of the most beautiful

structures at The Rocks.

The bee house, and the manuscripts for both the Fortnightly paper and the book version prepared for the Glessner grandchildren. serve as tangible links to this important chapter in Frances Glessner’s life.

Wouldn’t

she be pleased to learn how popular beekeeping is today?