In

May of 1903, Frances Glessner was asked to prepare a paper about her summer

estate in New Hampshire, known as The Rocks. The request came from The

Fortnightly of Chicago, a private women’s club founded in 1873 to enrich the

intellectual and social lives of its members; Frances Glessner had been a

member since 1879. Entitled “A Summer with Birds, Bees and Blossoms” (with a subtitle

of “A Summer Idyll of a busy woman and an idle man"), the paper was delivered on

November 12, 1903. Beautifully written, it focuses mostly on her close

observation of birds and her devotion to beekeeping. As it is rather lengthy,

and we wish to quote extensively from its pages, we will present this topic in

two articles, with Part I devoted to birds and Part II dealing with bees and

the paper’s reception as recorded in letters from her friends.

The

idea for a summer estate had its origins in son George’s severe hay fever. When

he was about seven years old, his doctor suggested that he be sent to the White

Mountains of New Hampshire for relief, as were other sufferers from around the

country. Accompanied by his mother’s sister, Helen Macbeth, George’s symptoms

disappeared upon arrival, and the family soon made the decision to summer in

the healthful environment of New Hampshire’s North Country. In 1882, after

spending several summers at the Twin Mountain House in Carroll, the Glessners

purchased their first tract of 100 acres nestled between the towns of Littleton

and Bethlehem. They completed their home, known simply as the Big House, in

August of the following year. It was significantly remodeled and enlarged by

Shepley, Rutan and Coolidge in 1899, as seen below.

The

Glessners would continue to spend summers at The Rocks until their deaths in

the 1930s, and both George and his sister, Frances Glessner Lee, eventually

made the estate their permanent home. In 1978, most of the property, which had

grown over time to more than 1,500 acres, was donated to the Society for the

Protection of New Hampshire Forests by Frances Glessner Lee’s two surviving

children. One portion of the estate is still owned and occupied by a

great-granddaughter of George and Alice Glessner.

(The remainder of this article is entirely in Frances Glessner’s own words.)

Let

me say in passing that this paper of mine is not a literary effort, but simply

a little group of stories and happenings within my own experience – “all of

which I saw, part of which I was.”

After

much consideration and a deal of search, we bought a farm – a rough and almost

barren hilltop, - thin soil covered with stones, somewhat forbidding in itself,

but with a genial summer atmosphere; an old red farm house, and the most

magnificent panorama spread out in every direction. The glorious White Hills of

Starr King* - white till the late

springtime, and with streaks of snow far into the summer, and verdure and gray

rocks everywhere marking the sky line, and the picture filled in by valleys

with green meadows divided by silver streamlets, the railroad track of

civilization on the far away edge, where we watch the train crawling along,

three sleeping villages, and the bluest sky and fleeciest clouds, with play of

sunshine chasing fleeing shadows over the whole, and the approach, the passing,

and retreat of sudden storms in the distance – all visible from our sunlight.

(*Note: Starr King, 1824-1864, was an American Universalist and Unitarian minister who, in 1859, published The White Hills: their Legends, Landscapes, and Poetry.)

It is

a trite saying that the spring air is vocal with bird music, “caressed with

song,” but it is a true one throughout the White Hills. Why were these ever

degraded to mountains? Save, perhaps, for that monarch of all, Washington, and

his lesser mate, Lafayette. And it is true also that these hills are bright

with one color following another, each in its own season, as the summer

progresses.

My

own little eminence is white with winter’s snows, tender green with early

spring, blue with violets and star grass, white again with clouds of blossoms on

old apple trees, pink in June with cinnamon and wild roses, later gay with

masses of yellow roses and scarlet poppies blooming together, and always and

everywhere soft warm gray with huge weather-beaten, lichen-covered boulders.

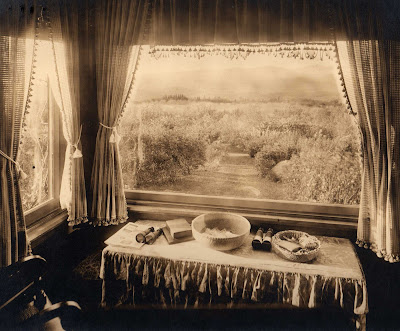

In

front of the big window of the big house, grows a goodly clump of stout young

birch trees which in midsummer is completely covered and bowed over with the weight

of a wild grapevine that has been encouraged to ramble thus over these little

trees; indeed the vine is given full possession, truthfully having its own

sweet will, for when in bloom the whole hillside is odorant with its fragrance.

Early

in the season and before the leaves are grown, there are many branches of this

vine sticking out in every direction, tough as wire, and most inviting to the

birds as perches. Here they sit and sing and swing, and swing and sing, and

there is no danger of the stiff fiber breaking or giving way. One morning in

early June the little lisp of an old friend announced the arrival of the cedar

bird, and after watching a while here was a pair of them lilting on the grape

vine in the very ecstasy of love, one of the pair with a bunch of twigs in her

mouth.

A

bunch of coarse blue yarn cut in lengths of about six inches was then hung out

on the family tree. Another pair of birds appeared. Blue wool went streaming by

in another direction. This second pair we watched, and with field glasses

traced them to a spruce tree on the opposite side of the house. From one window

we watched them gather the wool; from the other we could see them putting it in

place in the nest.

A

pair of robins raised an early brood in a spruce tree. Grievous to tell, the

young did not leave the nest alive, but furnished breakfast for some ravenous

crows.

This

disaster sent the birds nearer the house for the second family. Mrs. Robin

searched about the vine on the porch. She would nestle down in a thicket of

leaves and branches, evidently trying if it were well supported, secure from

interruption, and well hidden. A pair of these friendly little creatures built

a nest one spring in the cornice of the bee house. They were quite an

interruption to the work among the bees, for although tame and unafraid, still

I had to pop inside the closet when the mother came home with her mouth full.

Then, after she had fed her young, I would come out and go on with my work.

Some

days before her babies were ready to fly, I found in the walk a young robin,

far too callow to take care of himself; and, to make matters worse, he had

swallowed a little, stiff, prickly spear of growing grass. This stuck in his

throat and pinioned him to the ground. He was in anything else than a happy

condition. It was but the work of a moment to relieve him of the blade of

grass, - but what next? Well, I carefully tucked him in the nest in the bee

house with the four birds already there. When the old mother came home with her

mouth full, she looked the situation over carefully and thoughtfully, hesitated

a bit, then adopted the foundling, fed him, and was in a few days rewarded by

his being the first nestling to fly from home; he a big, strong, healthy robin,

for which he had his foster mother to thank.

Frances Glessner painted this china bowl. It no doubt depicts a nest she was observing at The Rocks.

For

many years, some human member (not humane member) – some human member of my

family has been in the habit of putting hemp seed on an old rock by the door,

but usually not until late in the season. This year, the rock has been strewn

with seed all summer and spring, and we have been rewarded by gay scenes;

indigo birds, purple finches, goldfinches, white-throated and striped sparrows,

and other seed-eating birds come there constantly and are growing quite tame.

And with them comes the chipmunk, or “hackey,” familiar, friendly, bold, confident in his quickness, ever alert and ready to fly from the first intimation of danger. But he is a glutton, a miser, and a wasteful spendthrift. He fills the pouches of his jaws with seed, a teaspoonful at a time, carries it off, buries it for future use, and promptly forgets where he buried it. Presently, I find little tufts of hemp growing up all over the plantations.

The

fly-catching warbler’s dart through the porch and almost under my chair, the

chimney swift’s beautiful flight and its sudden drop straight down into the

chimney, which is the only place he ever alights, the red-headed woodpecker’s cling

to a mullein stalk while I walk slowly up – confiding acts like these make the

birds a part of my family.

These

same chimney swifts are a great anxiety as well as pleasure. At the first whirr

of wings in the chimney out goes the fire in that room, comfort indoors or

discomfort. They persist in raising two or more broods in the same nest, and likely

on account of the nest becoming weak from age and use, one brood is sure to

tumble down into the sitting-room fireplace to the parents’ sorrow and mine. It

is said that the young birds can clamber up the chimney sides unaided, but ours

have not done so.

To

tell you about all of these feathered friends would be like repeating the check

list of birds of Northern New Hampshire, as this region is a great and favorite

breeding ground for many birds. Dr. Prime, Mrs. Slosson, Bradford Torrey, and

Mr. Faxon have found and checked one hundred and twenty distinct varieties in

the neighboring town of Franconia, and we have checked about ninety-six on our

own hill.

These

White Hills are teeming with memories of Starr King, Henry Ward Beecher,

Phillips Brooks, Dr. Prime, Charles Dudley Warner, and other literary folk.

Mrs. Slosson’s Fishin’ Jimmy whipped the streams about Franconia. The scene of

Jacob Abbott’s Franconia stories of Beechnut and Malleville is said to be here.

Hopkinson Smith’s Jonathan Gordon lived but a few miles away. Artists and

scientists, men of letters and of affairs, soldiers and statesmen, and

financiers and ministers of Christ, travelers and home-keepers, have broken

bread in my dining-room, poets have sung under my shingles, invalids have wooed

and regained health, tired men and women have sloughed off weary cares here,

and never a one of them all but has succumbed to the witchery of the place. Oh,

the luxury of loafing, the delight in the absence of responsibility, the

comfort of sitting still in sun or shade, or yet in rain.

(Part II will be posted in September)