Frances Glessner was introduced into Chicago society in the fall of 1897, exactly 125 years ago. Events unfolded quite rapidly following her return in July from a grand tour of Europe. She soon met and fell in love with her future husband while at her parents’ summer estate, The Rocks, in New Hampshire. After returning to Chicago in October, plans were finalized for her debut, which took place the day before Thanksgiving. Exactly one month later, her engagement was announced. She was married in February 1898, and by the end of that year had given birth to her first child.

The planning of a formal debut for girls turning 18 grew in popularity during the 19th century. In England, members of the aristocracy spent months planning for the event which culminated in presentation at court before the Queen. In America, the rituals could be almost as elaborate, with the dress (always white to portray purity), flowers, reception, and guest list all carefully considered. Autumn was the most popular time for the debut as it introduced the young woman at the beginning of the social season, providing the opportunity for countless dinner parties and dances at which to meet potential suitors. The goal was to secure a proposal of marriage by the end of the first or second social season.

Frances was actually 19-1/2 when her debut took place, due to the fact her parents sent her on a grand tour of Europe in May 1896, just two months after she turned eighteen. Accompanied by her maiden aunt, Helen Macbeth, the tour lasted fourteen months and upon her return to the United States on July 29, 1897, she joined her family to spend the remainder of the summer at The Rocks. A letter from her mother, penned on July 4, hinted at her change of status – she was no longer the girl Fanny, but the young woman Frances. Her mother wrote, in part:

“You are

grown up now – are no longer a child – we shall be good friends now. I shall

depend upon you, and you will help me and let me rely upon you. You are through

with the school room and are ready to take your place with me and to take on

responsibilities. Heretofore, your father and I have planned for you. Now you

can take the liberty which belongs to a young lady and to our daughter.”

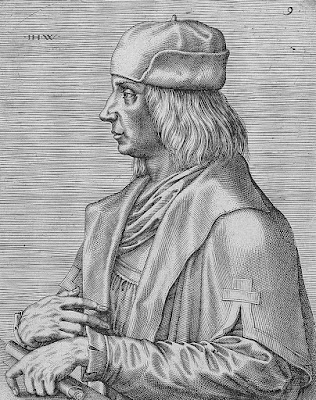

It was while

at The Rocks that she came to know Blewett Lee, her future husband. He was

eleven years her senior and had come to know the family through his friend

Dwight Lawrence, one of George Glessner’s closest friends. Blewett was a

promising young attorney and a professor of constitutional law and equity at

Northwestern University, and quickly endeared himself to Frances, and the rest

of her family. On October 17, less than a week after the family had returned to

Chicago, he asked the Glessners for Frances’s hand in marriage.

“Mrs. John J. Glessner and Miss Glessner of 1800 Prairie avenue will give a large reception on the afternoon of Nov. 24 from 3 until 6 o’clock. The affair will serve to introduce Miss Glessner.”

The date would have been carefully considered to avoid any conflicts, as Frances Glessner’s journal notes numerous debut parties during the month to which she was invited. On November 23, just one day before her daughter’s debut, she recorded attending the debut for Marion Thomas, the daughter of Chicago Orchestra conductor Theodore Thomas, where she formed part of the receiving party.

Frances Glessner carefully recorded the details of her daughter’s debut in her journal:

“Wednesday, the day was given up to the debut party. The flowers commenced to come in early in the morning. I had two men here from eleven o’clock on arranging them. We massed them on the library table and book shelves. There were huge vases of American beauties which reached almost to the ceiling and these were put on the south and east end of the table and the bouquets graduated down toward the door. It was a splendid sight. She had flowers from sixty persons.

“Frances’s dress was white crepe de chine with an embroidered polka dot all white. She wore a bunch of lilies of the valley which Mr. Lee sent her and three pink rosebuds from my bouquet in her hair. Miss Hamlin wore a blue and white silk and carried a bunch of white roses and one of crimson sent by John and George.

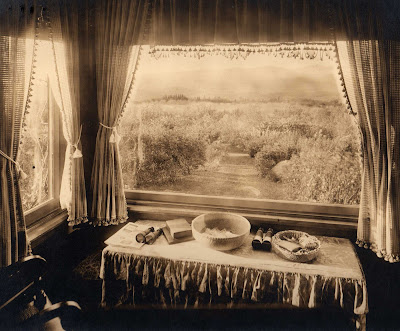

“I wore a

green watered silk and velvet. There was a large number of guests. Frederick

ran the dining room and hall and did it splendidly. We had three bunches of

white chrysanthemums in the hall and one on the piano, American beauties on the

sideboard and one on each side of the table in the dining room. We had a small

narrow table across the bay window. This had a white cloth which reached to the

floor. This was festooned with delicate green and pink rosebuds. We had no

assistants and no one to preside at the table. It was a pronounced success in

every way.”

“Miss Glessner, the only daughter of Mr. and Mrs. J. J. Glessner of 1800 Prairie avenue, made her debut in society yesterday afternoon at a tea from 3 until 6 o’clock. Mrs. Glessner was assisted by her guest, Miss Hamlin of Springfield, O. Mrs. Glessner and Miss Glessner will be at home Tuesdays during the winter.”

(Notes: “Miss Hamlin” was Alice Mary Hamlin, who would become George Glessner’s wife in June 1898. “Frederick” was Frederick Reynolds, who had served as the Glessners’ butler since October 1891. The Tuesday “at homes” referred to the social custom of Frances Glessner and her daughter being at home every Tuesday afternoon to receive callers.)

The day

after the debut was Thanksgiving Day, and in a distinct step away from formal

society, Frances and her brother and their friends attended a 1:00pm football

game between the Universities of Michigan and Chicago held at the Coliseum, 1513

S. Wabash Avenue. A dinner for sixteen took place in the evening.

On Friday, December 10, Frances attended her first formal ball:

“In the evening, Frances went to her first ball. She wore a charming gown of white tulle with a delicate garnishing of pink roses and green leaves. A pink rose in her hair. She was sweet as a peach. Mr. and Mrs. Chauncey Blair took her. John went after her at 12-30. Unie too went to help her. Mr. Lee went. Frances danced every time and was not very enthusiastic over balls when she came home.”

(Note: “Unie” was Unie Iverson, a servant).

Just six days later, the Glessners hosted a dinner dance for their daughter, with elaborate preparations requiring the relocation of much of the first floor furniture.

“Thursday we gave our dinner dance. We cleared the dining room and parlor of every piece of furniture – took down the curtains, took off doors, etc. The side board and piano were put in the hall and covered with old embroideries and brocades and used for favor tables. We arranged the favors on them and then covered them all up with Japanese parasols opened. The dining room was hung with festoons of green wild smilax and at the lowest point of each festoon we pinned a big bow of pink satin ribbon with long ends. Small rosettes of the same ribbon were put in the greens between the bows. These bows were given the dancers for their last favor.

“Johnny Hand and his orchestra of eleven pieces were in the hall between the stairway and the fireplace. Mr. Bournique came himself and brought his man to put the floors in the best condition. Our bedroom was used as a store room for furniture. The guests came in the drive way and up the winding stairs. There were forty two at dinner. We seated them at small tables in the parlor and dining room. We had a bunch of pinks on each table. After dinner, these pinks were put on the parlor mantel. The camp chairs were all covered with white muslin covers. The chairs were paired off and the numbers were painted on good sized cards and tied on the chairs.

“The dining room was absolutely clear. The red curtains were dropped and the green drapery and bows were on those. Mattie Williamson helped us all day. We had a nice dinner and at twelve o’clock a nice supper. The party broke up at two o’clock. We have been very much complimented over the party.”

The Inter Ocean reported the next day:

“About thirty young people were entertained at dinner by Mrs. J. J. Glessner of No. 1800 Prairie avenue last evening. Later, the cotillon was danced. The affair was in honor of Miss Frances Glessner, a recent debutante.”

The social events for Frances continued, the week leading up to Christmas being representative.

Monday, December 20

Frances

and her mother paid calls on the North side. In the evening, Frances attended a

dinner at the Lake Shore Drive home of Mrs. E. F. Lawrence and then the first

of the Marquette dances. The dance took place at the Germania Club on Clark

Street, just south of North Avenue. Attended by 150 people, the dance was

considered one of the important events in the social calendar for the winter

and inaugurated the season of subscription dances. The club hosting the dance was

composed of “young married people and young maids and bachelors who are prominent

socially on both the North and South Sides.” Frances’s father went after her at

midnight, at which time supper was served and the evening concluded with a

german. They came home about 3:00am, Frances noting she had “a fine time.”

(Note: A german,

also known as a cotillon, was a popular group dance, usually performed to waltz

music. It incorporated elaborate props and favors, such as those mentioned in

the Glessner dinner dance of December 16.)

Tuesday, December 21

Mrs.

William W. Kimball, 1801 S. Prairie Avenue, gave a luncheon for Frances. In the

afternoon, mother and daughter had about thirty callers.

Wednesday, December 22

Frances

hosted a “young ladies luncheon” for twelve. In the evening, Mr. Isham gave her

a dinner at his North side home.

Thursday, December 23

Mrs. A.

A. Sprague, 2710 S. Prairie Avenue, gave a luncheon for Frances.

Friday, December 24

Frances

dined at the home of Norman Ream, 1901 S. Prairie Avenue. His daughters, Marian

and Frances, would both serve as bridesmaids at her wedding. Frances’s

engagement was announced to the extended family.

Frances Glessner’s time as a debutante was active, but short lived. On February 9, 1898, just two and a half months after she was introduced into Chicago society, she married Blewett Lee. A future article will detail the events leading up to and including their nuptials, which took place in the parlor of her parents’ Prairie Avenue home.