This month

marks the 100th anniversary of the death of Bryan Lathrop. Amassing a fortune in real estate and the insurance

business, he became an extraordinary philanthropist in Chicago, supporting

numerous organizations. It was through

his long-time service to the Chicago Symphony Orchestra that he and his wife

Helen became close friends with the Glessners.

Bryan

Lathrop was born in Alexandria, Virginia in 1844. His family moved to Chicago at the outbreak

of the Civil War, Chicago being the home of his uncle Thomas Barbour

Bryan. Lathrop was sent to Europe to

study and did not return to Chicago until 1865.

It was during his years in Europe that he developed a deep appreciation

for art, culture and landscape design, which would guide his future

endeavors. He later noted:

“In Europe (the intelligent traveler) sees

almost everywhere evidences of a sense of beauty . . . In America, almost

everywhere he is struck by the want of it. . . In this new country of ours the

struggle for existence has been intense, and the practical side of life has

been developed while the aesthetic side has lain dormant.”

Upon his

return to Chicago, Lathrop joined his uncle’s real estate investment

practice. The two men shared a great

deal in common, including their appreciation for landscape gardening. As such, it is not surprising that Bryan

involved his nephew in the development of Graceland Cemetery, with Lathrop

joining the board of managers in 1867. When

his uncle moved to Washington in 1877, Lathrop became the president of the

board, guiding the development of the cemetery until his death nearly forty

years later.

Almost immediately, Lathrop

engaged the services of a civil engineer by the name of Ossian C. Simonds, who

would go on to become one of Chicago’s most important landscape

architects. Together they shared an

understanding and appreciation for naturalistic landscapes, and their work at

Graceland had a profound effect on not only the cemetery, but the development

of landscape architecture in the United States.

Lathrop

became an early advocate for the development of parks in Chicago, and as vice

president of the Lincoln Park board, led an effort to extend that park along

the shore of Lake Michigan supporting the concept of naturalism in its design.

In 1891,

Lathrop and his wife Helen Aldis, whom he had married in 1875, commissioned

Charles Follen McKim, of the firm McKim, Mead and White, to design their home

at 120 East Bellevue Place. Completed in

time for the World’s Columbian Exposition in 1893, the house was described by

architect Alfred Hoyt Granger as “the most perfect piece of Georgian

architecture in Chicago.” McKim came to Chicago

in early 1891 regarding his design for the Agricultural Building at the Fair,

and it was at that time that he and Lathrop were brought together. One of the few buildings in Chicago designed

by the firm, the design brought Georgian Revival to the Gold Coast, and in less

than a decade, it was the predominant style.

(The house has been owned and occupied by The Fortnightly since 1922,

and was designated a Chicago landmark in 1973).

Vauxhall Bridge, 1861; James Abbott McNeill Whistler

(Collection of the Art Institute of Chicago)

(Collection of the Art Institute of Chicago)

Lathrop

was a sophisticated and well-respected art collector, and the home was filled

with his treasures. Of particular

significance was his collection of the works of James Abbott McNeill Whistler,

the largest in the country.

Bryan Lathrop

became a trustee of the Orchestral Association in 1894 and four years later was

named vice president. In 1903, he was

elected president and served in that capacity until his death. It was under his leadership that the

orchestra moved into its new home, Orchestra Hall, and that the current name,

the Chicago Symphony Orchestra, was adopted in early 1913.

First program using the Chicago Symphony Orchestra name, February 1913

Lathrop

was a co-founder of the Chicago Real Estate Board, and developed an excellent

reputation for handling large estates both in Chicago and in the East. His other philanthropic activities included

the Chicago Relief and Aid Society and the Newberry Library.

Lathrop died

from heart disease at his Bellevue Place home in 1916. As noted in Illinois, the Heart of the Nation by Edward Fitzsimmons Dunne:

“Bryan Lathrop, who died May 13, 1916, was a

wealthy, generous, and public spirited citizen to whom the people of the city

were indebted during his life time and since for his constructive work in

behalf of several of Chicago’s cultural and philanthropic institutions.”

The

funeral service was held in the chapel of Graceland Cemetery. Frederick Stock, conductor of the Chicago

Symphony Orchestra, cancelled their concert in Buffalo, New York and returned

to Chicago in time for the funeral. Edgar

Lee Masters wrote a commemorative poem about Lathrop specifically noting his

support of music in Chicago, which was published in Poetry magazine.

Lathrop’s

bequests were numerous including $700,000 to the Orchestra for the establishment of the Civic Music Student Orchestra, the predecessor of the current Civic Orchestra. It was the largest

gift ever made to the Orchestra up to that time. (The orchestra also established the Bryan

Lathrop Memorial Scholarship Fund in his memory, using a large gift from his

sister Florence, the wife of Thomas Nelson Page, author and U.S. ambassador to

Italy.) His large collection of Whistler

artworks was given to the Art Institute of Chicago and his library went to the

Newberry. Additional bequests were made

to United Charities and Children’s Memorial Hospital.

Bryan

Lathrop was buried in a large landscaped plot at Graceland Cemetery, with only

a small unobtrusive headstone marking his grave. Helen Lathrop died in 1935 at her summer

home in Bar Harbor, Maine, and was interred beside her husband.

A TRIBUTE TO FRANCES GLESSNER

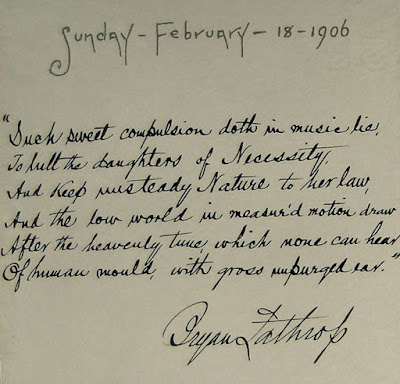

In 1905,

Bryan Lathrop was asked to submit a page to the calendar being prepared by the

Monday Morning Reading Class as a surprise for Frances Glessner. It was presented to her on her birthday,

January 1, 1906. For his page, Lathrop selected

an excerpt from “Arcades,” a masque written by John Milton in 1634 to honor

Alice Spencer, the Countess Dowager of Darby, on her 75th

birthday. The selection of this excerpt

says a great deal about Lathrop’s respect for Frances Glessner, as the piece

extols the subject as being far superior to other noble women. The excerpt reads:

“Such sweet compulsion doth in music lie,

To lull the daughters of Necessity,

And keep unsteady Nature to her law,

and the low world in measured motion draw

After the heavenly tune, which none can hear

Of human mold with gross unpurged ear.”