William Morris by George Frederic Watts, 1870 (National Portrait Gallery, London). The Glessners owned a photographic copy of this portrait.

A visit to

Glessner House reveals the inseparable connection between the designs of

William Morris and of Frances Glessner’s decoration for her new home. It has

often been said that the Glessners were a bit ahead of the curve in Chicago in

embracing the use of Morris & Co. wallpapers, textiles, and rugs, although

such items were gaining favor on the East Coast. There is little surprise here

as the Glessners were hardly followers of the popular trends of the day including

the reliance on anything of French origin. Instead, they actively studied and

developed an aesthetic of their own that is still well reflected in their carefully

preserved home.

This leads

one to ponder what the average Chicagoan would have known about William Morris

in the 1870s and early 1880s. In this first of three articles focusing on

Morris, we will look to the Chicago Tribune to see what was written

about him, only to discover that the decorative arts was only a small part of a

larger dialogue that included Morris as poet and Socialist.

The

Defense of Guinevere

One of the

first references to Morris appears in a review of new volumes of poetry in the

Literature column on May 22, 1875. A reprint of The Defense of Guinevere,

and Other Poems had just been released “without alteration from the edition

of 1858.” The reviewer noted that “admirers of the noble narrative poems, ‘The

Life and Death of Jason,’ and ‘The Earthly Paradise,’ will read with interest

the volume of Mr. Morris’ earliest metrical compositions.” The reference to

other well-known poems of Morris is followed by the note that his first works,

which received less attention at the time of their release, as he was an

unknown at the time, were now worthy of a second look, no doubt the reason for

the reprint. Of the collection, the reviewer concludes, “Most of these embalm

in verse the pleasing legends of King Arthur and his knights of the round

table, while all of them show the author’s remarkable command of the simple,

pellucid Saxon.”

Morris

returned to the collection of poems in 1892, when it was reprinted as one of

the first volumes published by his renowned Kelmscott Press. Many scholars have

noted Morris’s ongoing interest in the story and have made the connection

between the love triangle of Arthur, Guenevere, and Lancelot to a similar

triangle composed of William Morris, his wife Jane, and their friend, the

painter Dante Gabriel Rossetti. This final edition under Morris’s own hand,

shown below, is beautifully printed with woodcut borders and initials.

Aeneids

of Virgil

Morris was

also known for his translations and later in 1875 published his complete

translation of Virgil’s Aeneid, the epic Latin poem composed between 29 and 19

B.C. It was no small feat – the original is composed of 9,896 lines of verse

written in dactylic hexameter. The review in the Tribune quotes from the

Graphic which stated, “it is almost impossible to conceive of a version

more fluent, rhythmical, and supremely beautiful.”

The review

then goes into a rather extended discussion of Morris’s use of tobacco, noting

that “It is an interesting fact that Morris always writes under the influence

of ‘the baneful weed’ – tobacco. . . When the smoke is thickest, the poetry is

best.”

Household

art

In the May 14,

1876 edition of the Tribune, we find the first mention of Morris as

decorator, in this case for his wallpaper designs. In an article entitled

“Household Art” written by John J. McGrath, the owner of Chicago’s leading

decorating firm, he notes:

“I have

procured, by direct importation, a large stock of the Morris and Dresser

papers, being the only examples of these designs to be found in this country,

executed under the immediate supervision of these ‘art specialists,’ and far

excelling in purity of drawing and beauty of coloring anything heretofore

presented to the disciples of artistic truths, I cordially commend them to the

notice of all who are desirous of escaping from the thralldom of ill-conceived

and badly executed designs in wall dressing.”

It is

interesting to note that Frances Glessner was a regular customer of McGrath,

acquiring wallpapers for her Washington Street home at exactly this time, and

probably later for the Big House at The Rocks as well. This would have been her

introduction to Morris’s designs, although there is no evidence that she

considered any Morris wallpapers until 1883, as we shall see next week.

The

Morris mantra

“Have

nothing in your houses which you do not know to be useful or believe to be

beautiful.”

Morris’s

mantra is carefully written – the usefulness of an object is something that is

easily determined – a pitcher can hold and pour water; a clock keeps time. But

the beauty of an object is subjective, one person may believe it to be

beautiful, another may not. The concept became central to the Arts & Crafts

movement in highlighting the significance of the decorative arts, and the

importance of giving artistic consideration to the creation of all items – not

just fine arts, but the everyday objects that surround the average person in

their home.

An

interesting article from April 1882, which at first glance has nothing to do

with Morris, noted a large collection of “beautiful objects of art in the shape

of foreign bronzes, carvings, exquisite china and porcelain, old tapestries,

rugs, and odd bric-a-brac from every corner of the world, sent on to Chicago

from the well-known establishment of Sypher & Co., New York, and to remain

on view until next Wednesday, when it will be sold under the hammer.”

The

anonymous writer of the column spends considerable time describing many of the

objects and their inherent beauty. However, at the close, he turns to Morris

and his famous mantra (which was apparently known well-enough for the reference)

to consider both the beauty and usefulness of the objects. He writes:

“If everyone

heeded the advice of William Morris, to admit nothing into their houses that

they did not know to be useful and believe to be beautiful, some of these would

have to be excluded on the score of usefulness.”

William

Morris the preservationist

Morris was

deeply concerned about the state of preservation in the latter half of the 19th

century in England. In 1877, Morris and several friends formed The Society for

the Protection of Ancient Buildings in response to what he viewed as “destructive

restoration.” This process involved removing later alterations to return buildings

to an idealized original state, which may or may not have ever actually existed.

Morris felt strongly that the later alterations were part of the history of the

structure and advocated for repair and maintenance over the destructive

restoration practices. The Society still exists today, and Morris’s principles

are now widely accepted.

An article

in the February 28, 1883 Chicago Tribune reprinted comments made by Morris

regarding the announced demolition of the famous Ponte Vecchio in Florence,

Italy because it was deemed unsafe and might collapse during flooding. Morris’s

comments in part read as follows:

“We need

hardly point out, the unrivaled historical interest and artistic beauty of this

world-famed bridge, with its three graceful arches crowned by a picturesque

group of houses, over which is carried the long passage connecting the Pitti

and Uffizi Palaces. Not only the arches of the bridge, but portions of some of

the houses, are still preserved exactly as designed by Taddeo Gaddi, and built

in A. D. 1362 – an object of the greatest beauty both when seen close at hand

and as one of the chief features in the glorious distant view from San Miniato

. . . it certainly would not be beyond the skill of modern engineers to

underpin and secure the falling piers.”

William

Morris and his discontent

Morris wrote

and lectured extensively on the current state of art. In March 1883, a

paragraph in the London Life column of the Chicago Tribune, written

by special correspondent Robert Laird Collier, noted Morris’s discontent with

the current state of art. It is so well written that it is reproduced here in

its entirety:

“William

Morris has been talking about ‘blackguardly houses.’ This William Morris is in

his way a ‘regular caution.’ He is poet, painter, house-decorator, shopkeeper,

lyceum lecturer. He designs wallpapers, stuffs for curtains, carpets, and sells

these designs or the manufactured articles. He keeps a shop where one can get

the most artistic furniture, and, I believe, one can out of his shop furnish

one’s house from top to bottom. He has just been down to Manchester lecturing

at a conversazione of art and literary societies. He said he was so

discontented at the present condition of art and the matter was so serious that

he desired to make other people share in his discontent. He singled out

Bournemouth, a fashionable watering seaside resort, and said the houses of the

rich there were blackguardly! Whew! What would he say of Vanderbilt’s wallpaper

with its diamond dust! What would he say of a Chicago ‘marble front’ house, a

‘back yard’ twenty feet by twenty, and an – alley. But thank God for the

iconoclast. He is a nuisance, but he comes before the revolutionists, and the

revolutionist comes before the reformer.”

The term

‘blackguardly,’ not widely used today, referred to something lacking principles

or scruples, W. M. Thackeray (author of the 1848 novel Vanity Fair) referring

to it as “the tyranny of a scoundrelly aristocracy.”

Morris

the Socialist

The

reference to Morris as iconoclast was appropriate. Most of the references in

the Chicago Tribune by the mid-1880s referred not to his work as

house-decorator, but to his belief in Socialism, of which he was a leading and

outspoken proponent. In February 1885, the Chicago Tribune reprinted a

song written by William Morris entitled “The March of the Workers” that had

just been published in the English Socialist journal, the Commonwealth.

Sung to the tune of “John Brown” (the same tune used for the Battle Hymn of the

Republic), it consisted of eight verses and chorus. Beautifully written and

displaying his talents as a poet, we reprint here the first and last verse plus

the chorus.

“What is

this, the sound and rumor? What is this that all men hear,

Like the

wind in hollow valleys when the storm is drawing near,

Like the

rolling on of ocean in the eventide of fear?

‘Tis the

people marching on.

“On we march

then, we the workers, and the rumor that ye hear,

Is the

blended sound of battle and deliv’rance drawing near?

For the hope

of every creature is the banner that we bear,

And the

world is marching on.

Chorus:

“Hark, the rolling of the thunder!

“Hark, the rolling of the thunder!

Lo, the sun!

and lo, thereunder

Riseth

wrath, and hope, and wonder,

And the host

comes marching on.”

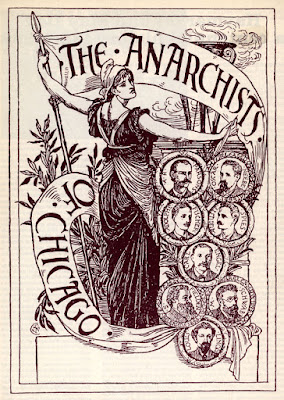

William Morris

the Socialist was quoted even more frequently in the newspaper following the

Haymarket affair/riot in May 1886. A particularly strong statement, issued in

the Commonwealth by Morris on November 12, 1887, the day after four of

the “anarchists” were executed was addressed “To the Well-to-Do People of America,”

and read in part:

“If you are

sure that henceforward the workingmen of your country will live placid and

happy lives, then you need think no more of the murder you have committed, for

a happy people cannot take vengeance, however grievously they have been

wronged; but if it be so with you, as with other nations of civilizations that

your workers toil without reward and without hope, oppressed with sordid

anxiety for mere livelihood, depraved of the due pleasures of humanity; if

there is yet suffering and wrong amongst you, then take heed; increase your

army of spies and informers; hire more reckless swashbucklers to do your will;

guard every approach to your palace of pleasure without scruple and without mercy,

and yet you will but put off for a while the certain vengeance of ruin that

will overtake you, and your misery and suffering, which to you in your

forgetfulness of your crimes will then seem an injustice, will have to be the

necessary step on which the advance of humanity will have to mount to happier

days beyond . . . You have sown the wind, you must reap the whirlwind.”

William

Morris a bit soured

By now we

have seen that William Morris was a man of strong opinions on a range of

topics. To close this week, we return briefly to his thoughts on art. Perhaps

of most interest is how he is introduced in the first sentence of a short Tribune article from May 1886 –

poet, Socialist, and artistic designer – in that order. One cannot help but

wonder if he would have introduced himself the same way. His quote, from a London

talk given a few days earlier:

“During the

last forty years people have conscientiously striven to raise the taste in art,

yet the world is growing uglier and more commonplace.”

NEXT WEEK

We do not

know the extent to which Frances Glessner was aware of William Morris’s

Socialist beliefs, or if she read his poetry, but in 1883 she began to study

his views on art. The commissioning of H. H. Richardson to design the Glessner

home in 1885 significantly strengthened that interest.

No comments:

Post a Comment